Juan Flores’s Salsa: A Never Ending Conversation

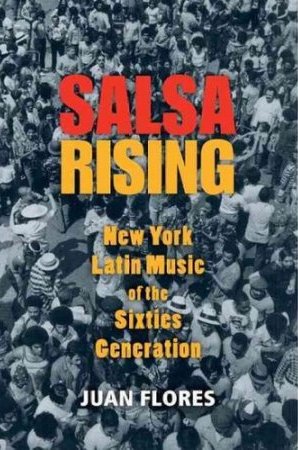

Imagine you are at the Tritons, “a very modest, small-scale social club” of the Bronx, October 1958, and “some piercing flute sounds [you] to a room” where Charlie Palmieri met Johnny Pacheco a few years before la pachanga became the new trend, the new New York sound, that in less than a decade will conquer markets around the world branded as salsa. To those specific locations of New York Latin music history, Juan Flores guides the readers in his posthumous Salsa Rising: New York Music of the Sixties Generation (Oxford 2016). In the first New York Rican history of salsa, Flores charmingly narrates the backbone stories of the encounters and the places, settings, communities, and most of all, the musicians as workers who generated one of the most notably cultural remittances that Latin@s have spread through Latin America.

Imagine you are at the Tritons, “a very modest, small-scale social club” of the Bronx, October 1958, and “some piercing flute sounds [you] to a room” where Charlie Palmieri met Johnny Pacheco a few years before la pachanga became the new trend, the new New York sound, that in less than a decade will conquer markets around the world branded as salsa. To those specific locations of New York Latin music history, Juan Flores guides the readers in his posthumous Salsa Rising: New York Music of the Sixties Generation (Oxford 2016). In the first New York Rican history of salsa, Flores charmingly narrates the backbone stories of the encounters and the places, settings, communities, and most of all, the musicians as workers who generated one of the most notably cultural remittances that Latin@s have spread through Latin America.

Following the working class point of view characteristic of his writings since his days at the beginning of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Flores visualizes salsa’s genealogy through the contrasting differences between Cuban and Puerto Rican communities’ experiences in New York between 1930 and 1975. So he proposes the forking paths of success obtained by Moisés Simons’ “El Manisero” —recorded by Don Azpiazú’s Havana Casino Orchestra and Antonio Machín— and Rafael Hernández “Lamento Borincano” as points of departure that exemplifies the contrasting differences between the Cuban and Puerto Rican cultural production during the first decades of the 20th century. Flores points out that although both songs tell stories “about economic transactions,” Simons’ is “an invitation to sensual delights” which eventually corresponded to the “crossover” stories of Cuban Music in Latin Jazz and Mambo. In contrast, “Hernández’s signature song evokes real-life suffering and struggle, disillusion, pride, and nostalgia for a distant homeland” (4), which through “a hundred of versions” spread this romantic sentiment through Latin America, and its guitar trio’s ensemble emerged as the most precious Puerto Rican music on both sides of the ocean during the Mambo craze.

Salsa Rising brings to the scene the contrast of the uptown “more grassroots music of the city’s expanding Latino communities” (12), whose tastes oscillated from mambos and sones to boleros, guarachas, décimas, plenas and aguinaldos, played by tríos in small clubs and family parties in the Bronx, many of which were recorded in New York and filled the juke boxes all around Puerto Rico, as Pedro Malavet Vega has observed. Then, evading to fall into binary essentialist oppositions, Flores explores the rise of salsa as the new cultural production of the Sixties generation of New York Latin community, mostly composed by the Puerto Rican working class migration of the 1940s and 1950s, and “once the ‘umbilical cord’ to Cuba was severed” (38).

Salsa Rising brings to the scene the contrast of the uptown “more grassroots music of the city’s expanding Latino communities” (12), whose tastes oscillated from mambos and sones to boleros, guarachas, décimas, plenas and aguinaldos, played by tríos in small clubs and family parties in the Bronx, many of which were recorded in New York and filled the juke boxes all around Puerto Rico, as Pedro Malavet Vega has observed. Then, evading to fall into binary essentialist oppositions, Flores explores the rise of salsa as the new cultural production of the Sixties generation of New York Latin community, mostly composed by the Puerto Rican working class migration of the 1940s and 1950s, and “once the ‘umbilical cord’ to Cuba was severed” (38).

It is in this way that the Tritons Club counter acts and crosses with the Palladium, where the Big Bands of Machito, Puente, and Rodríguez competed at the peak of the Mambo madness. This Jew-owned “social club on Sothern Boulevard in the Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx” (38) was the place not only of Charlie Palmieri and Pacheco’s first encounter that led to the pachanga craze, but this was the club that Eddie Palmieri rented for the rehearsals of what became La Perfecta, the original sound of “el Rumbero del Piano”, as Palmieri later was branded. There, at the Tritons—Flores highlights—was the “authoritative presence” of Barry Rogers, roaring with his trombone and dancing at the front of Palmieri’s group. Flores underlines that it was Rogers who brought to La Perfecta his “background experiences…in a range of bands and genres”, mostly jazz, and rhythm and blues. Finally, but no less important, it was at the Tritons that Al Santiago’s Alegre All Stars rehearsed and recorded what is the seed or the model of the Fania All Stars concert at Cheetah in 1971, for many considered it as the birthplace of salsa’s boom. Instead of following the narratives that situates salsa as only a continuum of Mambo and the big clubs of downtown Manhattan—that is to say, of Cuban music—Flores traces the rise of salsa from the Tritons in the early 1960s when Palmieri and Pacheco started the two different típico styles that characterize salsa, which continue—with its discontinuities—the “‘uptown-downtown’ dichotomy”.

So Flores criticizes the stories of salsa that limit its styles to Fania and Pacheco’s matancerization. The Triton, Palmieri’s típico, and the absolute emphasis on improvisation of Alegre All Stars present not only an uptown story, but underlines salsa’s communication with African American music styles and communities. So for him, the Latin boogaloo era represents an axis of these multiple-direction interactions. As in a previous essay, he presents the story of Latin Boogaloo as a new musical genre—“the equivalent, at a vernacular level, to Cubop in its time” (107)—adding up emphasis on its beginnings precisely at small clubs near to the Palladium, in the Bronx and in Brooklyn.

Reminding that Latin boogaloo was a crossroads of African American and African Caribbean musical traditions with the interventions of the musical industry, Flores traces the path of communication between African American and Latin communities which Ray Barretto and Joe Bataan followed, which eventually was excluded by the definition of Latin music, made precisely by Fania. And paying attention to salsa’s political sides, Flores also reminds the sex and drugs, peace and love, civil rights, Black Panthers and Young Lords “excitement[s] of the time”, all visible in pachanga, boogaloo, and salsa lyrics. As examples, Flores presents the Felipe Luciano reciting “Jíbaro / My Pretty Nigger” in Palmieri’s concert at Sing Sing, and the romantic and nationalistic “Canto a Borinquén” that many New York bands recorded. This reminder of how close salsa rising was to New York cultural and political localities, as the Harlem Renaissance is to Newyorican poetry, is definitely the most thrilling assertion of his extraordinary book.

In this direction, Flores considers Willie Colón as one of the main figures who stresses out salsa’s links with Puerto Rican communities in New York, including its nationalistic nostalgia. And if this was not enough, Flores highlights Colón’s Asalto Navideño as one of the most beloved products of salsa as one of the most visible and important cultural remittance of the New York Puerto Rican community, as he had already asserted in his previous The Diaspora Strikes Back (2009). But is because his career started at the borderline of the end of the boogaloo and the boom of the Palmieri and Pacheco’s típicos style, that Flores names Colón “the first lifelong salsa musician”.

So following this circulation of salsa as a cultural product I would love to have heard more about the importance of Puerto Rico as both musical market and imaginary homeland. Since the pachanga craze and through boogaloo and latin soul, in New York recorded albums, Puerto Rico was constructed as a tropical paradise and beloved homeland, as well as Panamá, Colombia and Venezuela as a sort of extended family. And at the time, the round trip travel between Puerto Rican communities —“a ambos lados del charco”—was more intensive than the previous decades and musical groups from both sides of the Atlantic competed for markets in New York and in many Caribbean cities. How important was this circulation in la guagua aérea —the “jala jala” from between Puerto Rico and New York—for the establishment of the Matancera style as the standard? Transiting this two-way path were Cheo Feliciano, Roberto Rohena, Richie Ray and Bobby Cruz, whose experiences in Puerto Rico was recognized in Our Latin Thing and the two albums Fania all Stars Live at Cheetah. And, though well recognized, I also would have loved to read more about Tite Curet Alonso, from Santurce, who extended and expanded those Colón’s barrio images, and underlined the similitudes and traced connections with Puerto Rican history, literature and racial discourse in the Sixties Generation. But maybe what I miss in the book responses only to my side of the Boricua zone experience and point of view.

Salsa Rising comes on as a closing of a long scholarly career dedicated to Puerto Rican studies, a period in which salsa has risen as main topic of the inclusion of popular culture in national discourse and scholarly research. It reminds me of the kind of interaction and dialogue with Juan that I will miss forever; and I also believe that I’m not the only one. I am sure this was the kind of conversation that he had with those “utterly indispensable sources” who helped him to articulate his views. I am sure that all of them has something to add to this discussion. To contribute with this never ending conversation, Juan left us with what along with Las memorias de Bernardo Vega, Jesús Colón: A Puerto Rican in New York, Down These Mean Streets, Snaps, Puerto Rican Obituary, Nilda, La Carreta Made an ‘U’ Turn, and a few others, is a Nuyorican Masterpiece.

*Publicado originalmente en Centro Voices.