Reflections on Vanessa Droz’s Permanencia en puerto (2019)

fotos por Doel Vázquez Pérez

I suspect that Vanessa’s poems may seem perplexing to the casual reader, as they did to me, because Vázquez’s photos are less a key to her poetry than a spark that fires up her own system of signifying images and their interrelationships. I recognize that the word “system” is misleading since a poet’s intuitive and imaginative world can hardly be reduced to rational categories. But I think we can discover consistencies that may illuminate some of the volume’s complexities. Though I will refer to most of the poems, I will focus on a number of them that seem to me particularly significant. For purposes of my discussion, I don’t always consider them in the order in which they appear in the poemario.

I begin with a general observation.

There is intense drama in these poems but it is, I think, existential rather than psychological. Rather than explore interpersonal relations or personal problems—though there are a few first-person poems that appear to do so—the poet prefers to investigate in her idiosyncratic way the universal themes, including aging and death and poetry itself and on numerous occasions using humor. Life is a struggle of the light (luz) against the shadows (sombras, tinieblas), but ultimately a losing one for someone who believes in nothing: Yo, que nunca he tenido fe en nada (El tiempo detenido). In fact, of course, she does believe in something: the poetic eye (ojo) which with the aid of myth and pre-history and word play can discern a transformed reality, and make this alternate truth not only bearable but beautiful.[1]

As I see it, the challenge she has created for herself is daunting but exhilarating: that of fusing two contradictory visions of reality, one light and life-affirming and one dark and deadly, an effort that is itself woven into the fabric of the poems.

De la casa y del patio

Candado

This poem, the opening one in this section De la casa y del patio, is a charming as well as a useful thematic introduction to the book. The photo in black-and-white above the poem shows an old door—or perhaps two doors—closed with a padlock that casts a shadow; on either side of the lock are old-fashioned metal ornaments.

La alhaja que separa los dos mundos

ríe muda entre triviales adornos.

Crea sombras como crea nostalgias,

puertas como crea cielos y alas,

portentos como define el cielo

cuando crea cuartos y salas.

Es arete en orejas dormida,

ajorca en atrapado lóbulo que aúlla,

zarcillo que una deidad violenta

para abrir, blanco y negro dibujado,

la casa donde el tiempo se detiene,

donde siempre ha estado detenido.

Nadie entra; solo el ojo que atrapa

la joya que hace lucir la caja

de Pandora como un juego de infantes,

como un lugar posible en la ciudad.

At first and even second glance, the photo of a decrepit door and rusting padlock appears to have nothing in common with the vivid, exuberant world that unfolds in this poem. The padlock becomes a jewel that separates these two worlds, the run-down house and the vision it inspires in the poet. It seems to awaken, laughing silently, then creates things like nostalgias and wings; turns into an earring that makes body parts like the ear and earlobe come alive; invokes a god; informs us that time has stopped in this house. Towards the end of the poem, we learn that it is the (poetic) eye (ojo) that has wrought this transformation. Throughout this poemario many of these idea-images and phenomena associated with poetic suspension of harsh reality will recur—wings, body parts that spring to life, gods and time that has stopped—and we will return to them. Here I want to stress that not only does this disembodied eye work to transform the world but—crucially—reminds us it is doing so, as here in the references at the end to un juego de infantes and un lugar posible en la ciudad. In short, the “eye” recognizes it is playing a game by creating an alternate place.

It’s noteworthy, I think, that this “possible place in the city” far from being dreamy and idyllic has a strong hint of violence. Consider the lines Es arête en oreja dormida, /ajorca en atrapado lóbulo que aúlla, /zarcillo que una deidad violenta/para abrir, blanco y negro dibujado, /. A subtle word play reinforces the sense of menace: ajorca—one of the various words for jewel referring to the lock—sounds like the verb, ahorca, while lóbulo sounds like lobo. A god “forces open” (violenta) the jewel/lock. But then the tension is relieved: no one can enter because the eye is in charge: Nadie entra; solo el ojo que atrapa / la joya …/ The repeated use of the verb atrapar reinforces the eye’s “capture” of the jewel/animal/god it has itself created. Violence whether suggested or real is a leitmotif woven into many of the poems, and whose significance we will examine towards the end of this essay.

Ni los fantasmas

The following poem, Ni los fantasmas, which accompanies the photo of a pair of rotting vertical wooden timbers, presents an alternative perspective: the “dark side” of an old house. This place is so infested with illness and evils, which are incomparably and humorously described, that even ghosts dare not show up. In fact, Death himself is inside sitting on a sofa, seemingly a bit bored, with a drink and a cigarette and a half-read book (of poetry). The poem concludes: Ni los fantasmas se asoman. /No podría con más muerte la muerte. Humor joins poetry in the struggle against life’s horrors.

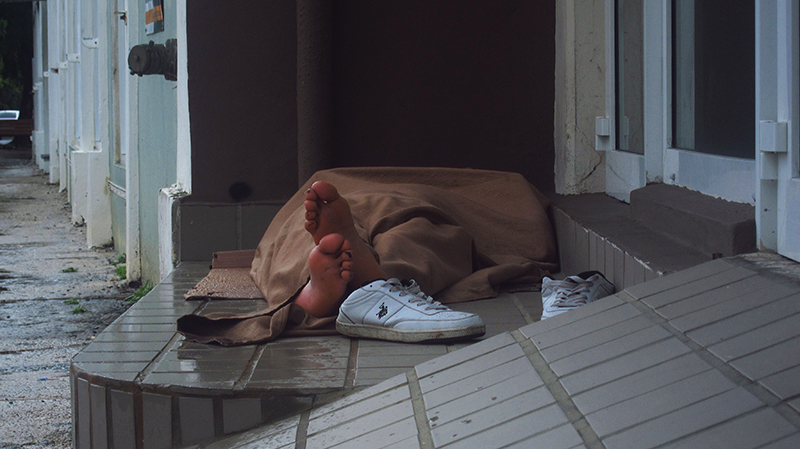

Niké

The poet also displays her humor in the following two poems. The first, Nike, projects a social concern of the author, which she treats here with sympathetic irony: the homeless in Old San Juan where she lives. The photo shows the bare feet of a vagabond asleep under a blanket on a door stoop; his two sneakers are nearby. The reader of course knows that “Nike” is a famous brand of sneakers (though those in the photo are of a different make). The poem refers to the notion of Nike, Greek for victory, and the ancient Olympic games presided over by the gods wherein the victor was crowned with laurel leaves. As in Candado in which a lock comes alive, in this case the bum’s foot and his shoe and then his body are the protagonists, the first mounting guard while the second sleeps pretending to be a shield. The body will tell the foot to return to the road where on different sidewalks there are other sleepers whose heads are crowned by laurel. But their only victory, when they awaken, will be los ojos vivos. In one sense, this suggests they will be lucky to survive to another day; but in another—given the transformative role of seeing for the poet—their eyes may somehow enable them to transcend their misery. For its part, the foot stammers that maybe someday it will have a winning lottery ticket, and the shoe swears to it, but is “delirious”. The poet invokes gods and myths along with the activist foot and shoes to unshackle her subjects and readers from harsh reality.

Parenthetically, I want to point out that feet and shoes are forceful presences in a number of poems, notably Los paseos de la Virgen, in the book’s second section Del puerto y el jardín, in which under a photo of reddish clouds, the poet relates how the Virgen strolls on the floor (piso) of the sky: El incendio se le quedó prendido / de sus zapatos ligeros. Las suelas/ dejan sus marcas, y alborotado, /las mueve el viento. Her steps set fire to the sky; the poet combines here several powerful image/ideas—sky, shoes, fire—that connote freedom from life’s travails. The title makes clear that the subject of the poem is less the Virgin than her footsteps.

Ama a tu mascota

This is the second poem displaying the poet’s gift for irony and humor, which accompanies the photo of an urban bus. There is a play on words since AMA is the acronym of Autoridad Metropolitana de Autobuses. The bus and even the sidewalk undergo an imaginative transformation: La guagua se deja llevar/pues es dócil como las aceras/que se dejan arrastrar por los caminantes/y acariciar por los vagabundos, / besar por los mendigantes/y los durmientes de ocasión. /Cuando la acera se levanta/ su rebelión es llevada hasta la guagua/ y allí, sobrecogida pero altanera, /es desenrollada por los viajantes. /Cada uno toma su pedazo, lo acaricia/ y lo hunde en su corazón como un huerto. There is a remarkable imagination at work here: the bus and the sidewalks come alive and enter into affectionate relation with the users as if they were mascots. Dogs as such feature prominently and very positively in two other poems, Escribir una historia and, in the second part of the book, Soledad de la sal.

Las manos de la cueva

This poem is I think key to comprehending some of the most important recurring images and concepts. The photo with it reproduces some graffiti on a city wall. There are three more photos of graffiti, each with its own poem, but I limit myself to the first.

A dónde va el trazo,

hacia donde se extingue su pálpito inseguro,

por cuales lienzos transita su intención exacerbada.

Mirarse las manos y descubrir (¿acaso dije describir?)

si en ellas hay algo,

si se esconde la muerte o, quizás,

la lucha diaria contra las fieras que,

con toda su contemporaneidad,

quieren devorarnos.

Con una plegaria al más allá pretendemos alejarlas

mientras volvemos a atizar el fuego,

a copiar nuestras manos,

las cenizas y los óxidos – polvos de la creación –

arrojados como arena entre los dedos.

Las copiamos, les insuflamos nuestro aliento,

las bendecimos con precarias palabras.

En ellas no hay nada que no sea el gesto,

el naufragio sobre la pared,

las falanges que viajan por la relamida piedra antigua,

la mano que se vuelve ala, pez,

abono o fuego y decide

permanecer en la cueva,

en el corrientazo de sus opciones.

Reacting to the graffito, the poet sees it as alive, going somewhere, in transit across some canvasses (lienzos). It makes her wonder about the dual character of our hands, whether they “hide death” or perhaps the daily struggle against “the beasts that want to devour us”. We learn this struggle is not just contemporaneous but stretches back to prehistoric times and caves that retain on their walls the marks of human hands. Suddenly we’re back in the cave with these early ancestors, uttering a prayer (plegaria) to the beyond to keep the beasts away as we stir up the fire, and are copying “our hands” on the walls using ashes and oxides—the dusts of creation—between our fingers. We infuse them with our breath (aliento), and bless them with palabras precarias. The reader may recall God’s creation of Adam in Genesis, but here the work of creation is wholly human. Although the hand paintings are no more than a gesture, a “shipwreck” on the wall, finger digits (falanges) travelling over the smooth ancient rock, even so the hand has become a wing, a fish, fire, which are recurring images of freedom from mortality. Just as in Candado the eye created “a possible place in the city”, here the cave-dweller’s hand “decides” to remain in the cave conscious—as it were—of its options. In the author’s poetic world view, our biological and cultural evolution over eons of time as well as ancient myths provide historical validation and depth to our present experience.

Calistenia de la tiniebla

In this weird but compelling poem, the hand reappears as protagonist, in its other possible—and negative—role of “hiding death”. In fact, here it ends up strangling a victim. The photo above the poem is indeed menacing, a decrepit nighttime street with a small dark figure running in the background.

No hay que temerle a la tiniebla,

que es una sola y solitaria,

fraternal en sus avisos y solidaria,

como las enfermedades.

Mucho menos de noche,

cuando sus susurros

no llegan a ser palabras

y se escurren por la garganta

Hacia los dedos. La mano

recibe el donativo y hace

su calistenia, afina la vista

y sale tras la figura que transita

sin permisos en medio de la calle

justo después del mes de los huracanes.

La mano busca la garganta

que es tan frágil como sus falanges;

y la figura, el fantasma de la basura

y los desdenes, el espectro que hurga

entre los perros un manjar sin colmillos,

agradece, conmovido,

ese último aliento antes de sentir

-como si fuera el retrato de su madre

y de sus hijos en un colgante para el cuello-

temor por la tiniebla.

There are several points I want to make. First, the poem begins with a mesmerizing description of the hand receiving the wordless commission to kill from la tiniebla, doing its warm-up exercise (calistenia), then focusing its vision before taking off after the victim. There’s humor here despite the macabre scenario. Second, the nameless, faceless victim who is unauthorized to be in the middle of the street after the hurricanes (Irma, María?) and who roots in garbage bins for food along with dogs, sympathetically recalls the homeless person who will surely not win the lottery in Nike. And third, even as it kills its victim the hand is portrayed as a force for life. Thus, the victim feels grateful, moved, as the hand slides along his throat and he draws his last breath (aliento), perhaps even receiving a vision of his mother and children before experiencing at the very end temor por la tiniebla. This killer hand is associated with the same breath of life (aliento) that our ancestors put into the image on the wall in Las Manos de la cueva.

Astrágalo para una calle

This following poem also involves the dying or death of someone. It unfolds beneath a striking black-and-white photo of a cobble-stone street between a line of black buildings leading off into the distance to a narrow opening where we catch a glimpse of late afternoon sun. The poet addresses directly a figure with a “bloody face and head-down skeleton” in the hope “you” (tu) will try to maintain equilibrium in a street that seems to be participating in a shipwreck: Juro que la calle se movía/ – pez que salta, danza, pájaro que se sumerge -, /que las aceras bajaban y subían / hacia todos los puntos cardinales. Although motion and dancing are often part of the poet’s positive vocabulary—as in the undulating streets and sidewalk of Ama a tu mascota—here however the poem begins with motion that has gone haywire: fish and birds have exchanged roles. The person’s feet are losing their wings, the sun has been turned off, and he/she is entering into the night.

And yet curiously, the last parenthetical lines are positive: (Si no fuera por ese hueso, por solo ése/ que te ayuda tanto.). They refer to the ankle bone (astrágalo) of the title which has apparently been helping the person’s feet maintain balance even as he/she walks into the night and death. One recalls the assassin’s fingers in La calistenia de la mano caressing, as it were, the fragile neck bones of the victim, or the prehistoric fingers leaving their mark in La mano de la cueva: las falanges que viajan por la relamida piedra antigua, /. Though in this instance, the protagonist is the ankle bone, as we have noted the foot is as iconic and “spiritual” a part of the body as the hand. Indeed, the title of the poem celebrates this bone as if it were another body part that struggles against death; the curious word astrágalo has what could be called a “celestial” vibe (astro). In short, this bone also somehow extracts light from the dark theme of death.

Crucigrama

This is a novel poetic take on the interplay of light and shadows. The photo is of an abstract pattern of mostly white but some dark squares of light falling on a dark street; the sequence comes toward the viewer in a widening perspective acquiring a touch of yellow from the street’s curb as it moves off towards the bottom left.

Cuadricular la luz o cuadricular la sombra

es tarea imposible. La figura lo advierte

y pone palabras en cada sombra, en cada luz.

Ebria, entonces, de tanto alarde y nombramiento

-caminante del aire, surtidora de cielo-,

da los pasos para escaparse de la foto

(que es asfalto o es cristal, que es ventana o acera,

recuadro sombrío en que el sol traza una línea),

para llegar al borde, que es un potencial

camino, un destino fuera de la imagen,

un acantilado para ensayar el eco.

El damero expone sus opciones,

sombra y luz,

y la figura, alada, flota sin tocar

el lenguaje, que es también abismo, ceguera.

In this subtle poem, the protagonist—la figura—is invisible, more insubstantial even than la figura who is the victim in the last two poems. But the poet makes it come alive. Here the figure is the thought that arises upon seeing a pattern of light and shadow on the asphalt that looks like a crossword puzzle. The figure is aware that it’s impossible to turn the blocks of light and shadow into perfect squares, but plays with putting words into them. Drunk with the effort (ebria), “walking on the air and supplier of sky (cielo)”, the figure moves towards the photo’s edge which seems a possible path out of it. The sense of liberation is reinforced by its walking on the air, taking steps towards the impossible and, perhaps, transgressing the yellow curb. Now the puzzle turns into a checker board with two options, dark and light; the “action” ends with the “winged” figure floating above the options, for the moment free and happy. Like the “eye” in Candado, the figure experiences liberation by playing the game of possibilities. However, here the last two lines introduce the disconcerting option that the floating figure could “touch” “language” which is like the “abyss” of “blindness”. It’s disconcerting because to the reader it would seem that language is what poetry is about; how can it be like an abyss or still less, blindness, the antithesis of the poetic ojo? We’ll look at this paradox further on.

Let’s turn now to poems from the second part of the book, Del puerto y el jardín.

Honor de la paloma

Like Candado that initiated the first part of the poemario, Honor de la paloma is an extraordinary poem. The photograph inspiring it is of a pigeon sitting on a solid blue bollard or buoy in the foreground that juts out of the water of the bay, perhaps the bay of San Juan, while across the water in the distant background one perceives docks with cranes and cargo containers. The sky above the bird on the fixed buoy is cloudy.

Llegar a puerto no es garantía

de descanso.

Ni siquiera el ave

que se posa sobre un trozo de cielo

tiene sosiego o ancla en estos días.

Mira el mar y sabe que no es el mar,

oye los bocinazos de los barcos

que solo son arcos contra el agua,

mira el litoral que la industria anega

y sabe que no es industria, más bien

un deshecho, como detrito es

lo que otras aves, antes que ella,

han dejado sobre el firmamento

que hoy, para su honra, ella ocupa.

Pone atención al aire y al agua

y escucha sus plegarias, su cristal.

Sabe de sí misma muy pocas cosas,

pocas, pero certeras, exactísimas:

entre ellas, que siempre quiso ser gárgola

y que ahora, vuelta estatua de sal,

el mar la envidia y la desea;

que la bahía-luz que adormece-

es espejismo para navegantes.

Náyade, a esta ora la complace

que aún hay barcazas que persiguen

su silueta para tirar amarras.

Ella, cómplice, les advierte:

“El descanso no está garantizado”.

Whereas Candado introduced us to the Old San Juan cityscape with a photo of an old door in the city, so Honor de la paloma brings us to the bay and sea with the photo of a pigeon that has alighted on a buoy. The protagonist is the pigeon; birds are free spirits that exist between the land and the sky, though here it is momentarily at rest. But the poem begins as it ends with a warning: arriving in port does not assure rest (descanso), nor peace or anchorage even for a bird who sits on a “piece of sky” (un trozo de cielo) which presumably frees her from earth. We might say that we have here yet another version of the poetic game of transcendence that is aware it’s all a game but nonetheless real for all that, of the desire for rest from life’s struggles while simultaneously knowing there can be no true peace. Secure in this temporary identity, the pigeon frankly denies everyday reality: looks at (mirar) the sea but knows that it is not the sea, and that the industry on the shore is merely the detritus that other birds before her have left on the firmament (the sky) which it is now her honor to occupy. That “honor”, I think, is precisely this happy balance she has attained: resting on a piece of cielo while aware that it is not that and that life offers no permanent anchorage or peace.

It’s noteworthy how her perch on this “piece of sky” empowers her. Far from needing to pray, she listens to the prayers (plegarias) of air and water. To offer plegarias is an effort to ward off the fieras of life as in Las manos de la cueva, and can be a symptom of weakness and exhaustion, the forlorn hope for some sort of salvation from life’s struggles, as in the book’s title poem Permanencia en puerto, discussed below. She has exact knowledge, which seems to be a poetic balance that can be lost on the destabilizing sea of life (as we will see too in the same poem). What is her “exact knowledge”? It associates this bird with permanent monuments: gargoyles; a statue of salt; and a Naiad (Náyade). Thus, she knows she always wanted to be a gargoyle; that the sea envies and desires her now that she has become a statue of salt; and that the bay where she awaits the sailors as a Naiad with its promise of home port and rest for the sailors is but an illusion. Why these particular “monuments”? Let me speculate. Gargoyle, from the French gargouille, refers to the throat or body part that carries the “breath” of life (see La Calistenia de la mano); in architecture, gargoyles are mythical monsters on the roofs of Gothic cathedrals whose “necks” are water spouts that channel rain away from the walls it could damage. And, by becoming a statue of salt, the pigeon has in effect domesticated the ever unstable sea by condensing out its bitter salt, so that the sea itself envies and desires her. The final thing the pigeon knows for sure is that the bay is an illusion for the sailors. Assuming one more mythical identity, that of a Naiad or water spirit, she delights in (le complace) imagining that there are barges which think they can tie up (tirar amarras) by pursuing her silhouette. Then, with a sort of conspiratorial wink, she tells them: (Ella, cómplice, les advierte): “Rest is not guaranteed”. This pigeon’s powerful tools against the knowledge that life offers no guarantee of peace is her poetic vision and the calm irony that accompanies it.

Permanencia en puerto

This lovely poem is excruciatingly personal. The photo with it is apparently of the masts and rigging of two sailing ships set against a cloudy sky though with streaks of light showing through. The bodies of the ships themselves do not appear, and the lines of rigging and rope ladders of the one in the foreground are slanted at odd angles. Two notable differences distinguish this key poem from all the others in the book: its title is also the title of the whole poemario, and it’s the only poem located above rather than below the accompanying photo.

¿Qué línea usar para zarpar

si están todas trazadas en el agua?

¿Qué timón agarrar

si el mástil esgrime su aérea amenaza,

su histórica paciencia?

¿Dónde está el cielo, que las agujas del tiempo

ya no quieren permanecer en las brújulas,

que las gráficas del espacio se han desordenado?

Mejor me quedo en puerto

con la mirada puesta en el mar inexistente,

con un corazón que no sé donde colgar

de tan exhausto, de tan penitente.

Like Dante’s narrator, the poet has lost her way. She deploys a rich palette of significant idea-images and harsh consonants such as d, g, z, x, and the striking semi-rhyme inexistente…penitente to convey the picture of an exhausted traveler on life’s sea who can no longer find her way in a disordered world much less locate the sky (cielo), and so has decided to stay in port. The photo’s lines of a jumble of rigging askew against a mostly dark sky reflect her sense of confusion and loss; she lacks the “exact knowledge” that the pigeon/protagonist relied on in Honor de la paloma. So rather than risk shipwreck on the trackless ocean she thinks it’s best to remain in port though uncertain of where she can find a stable place to hang up (colgar) her exhausted, penitent heart. One wonders: Has the poet-narrator lost the self-assurance of the pigeon in Honor de la paloma who, sitting on her piece of sky, can accept there can be no rest, no peace; no “permanence”? Has she thrown in the towel?

Well, no. In my view, the poet gives us here a snapshot of the emotional downside of her poetic enterprise: when no blue sky appears, life seems disordered, and ageing and other defeats sap energy including poetic energy. It is the living embodiment of what the pigeon knows: there is no true peace. But notice there is no resignation here. The poet questions where the poetical navigational aides have gone but doesn’t affirm that they have failed. Presumably they may reappear, she may find a secure place for (donde colgar) her heart, regain her energy and reject the guilt (penitencia) which losing ground in the struggles of life entails. Moreover, despite that guilt and her exhaustion, the poet-narrator continues to fix her gaze on the “non-existent sea”, that is, her ojo is still capable of seeing beyond harsh reality just like the pigeon in Honor de la paloma who “looks at the sea and knows it is not the sea”. In short, she is still playing the life-and-death game of suspended options we discussed in Candado and Crucigrama, and which is quite clear in the last lines of Las manos de la cueva (notice the verb permanecer): /la mano que se vuelve ala, pez, / abono o fuego y decide / permanecer en la cueva, / en el corrientazo de sus opciones.

Moreover, disorder and confusion can be the quarry of creativity, and the author must know that this poem is itself a gem that ironically gives the lie to its subject of creative exhaustion. I think this may explain why she has not only placed it above the “disordered” photo but in fact made it the title of the book. [2] For what is “permanent” is not the despair but the poetic ojo that remains capable of overcoming it.

Still, we see in nearby poems that her other poetic protagonists are ageing and concerned with loss, even the birds which for her are symbols of freedom as well as nuestros ilusionados ancestros (Luz oriental). Let’s look briefly at two of them.

Plegaria del pelicano

There is a striking photo of a pelican standing on a wet beach, head down as if praying or looking at something on the sand. In the poem below it, we learn that the pelican is old, and that his constant prayer (plegaria) is to be able to continue to fly, to see the schools of fish below, dive down into the water and grab some without being himself grabbed in turn by something lurking in the water. For this bird—unlike the pigeon in Honor de la paloma—is confused: Los reflejos que produce el agua/ sobre la arena lo confunden. /Cree, /cisne venido a menos, /que camina sobre el cielo, / que se mueve en el cielo. He “sees” heaven but it’s just a reflection in the sea water at his feet. In effect, his illusion puts him at the mercy of the sea with its lurking monsters. The poem is a cautionary tale: the ageing bird thinks he can repeat the deeds of his youth and still believes he can “walk on the sky like a swan”. His prayers won’t help him, and death will catch him unawares: Así, todos los días, / aferrado a su plegaria, /va muriendo.

Estrategia de la garza

Not so unaware is the heron who is protagonist of the following poem. The photo which inspires it is quite different from that of Plegaria del pelicano. Whereas the pelican with head bowed looks down at the darkish watery sand, the white heron stands on a piece of driftwood looking off into an intense blue sky, reminiscent of the pigeon in Honor de la paloma que se posa sobre un trozo de cielo. The inconstant water and sea are nowhere in sight. This bird is also ageing but deals with it not with prayer but “strategy”: he has a game plan which avoids self-deception. Or at least the author gives him one: La realeza del vuelo le da la ventaja de los dioses, / su capacidad perpleja pero viajante. / Se posa sobre las briznas y hurga / en las raíces recién revueltas las larvas / de su infancia, los gusanos /de su adolescencia, las lombrices /de su madurez. Una cena completa /en medio de la edad dorada. … Unlike the pelican, this heron has no fear of going hungry because he flies “with the advantage of the gods”, his eyes spotting food below; he has a sort of awareness of inevitable aging and so “associates” the larva, worms and fleas with the different periods of life. And he has two other advantages going for him: his sinuoso cuello de interrogación (very evident in the photo) which implies the same difficult but life-saving questioning we saw in Permanencia en puerto; and his eyes (ojos) which help him discover como un farol the poetic “strategy” of the food sources corresponding to the different ages of life on the estuary below. The poem is particularly light-hearted, indeed tongue-in-cheek.

Asuntos del mar

Like Permanencia en puerto, Asuntos del mar is an intensely personal poem, in this case recalling the pain of a personal relationship of the poet that has ended. The photo is of a simple wooden bench on a beach at the edge of the sea.

Pongo la ausencia dentro de un frasco azul,

como corresponde a los asuntos del dolor.

Me quito los ojos y los coloco al lado

sobre la mesa reluciente.

No espero nada, solo la quietud que da la ceguera.

Antes, cuando nos sentábamos frente al mar,

las manos eran un columpio para la espera

y los ojos los guardianes del fuego.

“Siempre lo han sido”, me dijiste, pero yo

solo pensaba en estar sentada

y en esperar a que te fueras,

soñaba con el banco vacío.

No sin ti. Tan solo sin mí.

Así es el odio frente al mar.

This seems to be the story of a once happy relationship of the poet that broke down. Why? The vital fire on which it depended required that the poetic eye (ojo) remain aware of its impermanence, which the poet’s companion forcefully denies (she quotes him directly). The poetic nature of that fleeting happiness lies in the mention of their hands, here joined in a swing (columpio), a game but also a repetitive motion that recalls for our poet our continuity with human pre-history, as in this line from La soledad de la selva: /ancestros columpiándose en la selva/. In my interpretation, since poetry failed her with this companion, she has taken her eyes out and laid them on the table; her emotional state is a sort of numbness in which she hopes for nothing, only the quiet that blindness (ceguera) can give her. And yet, “poetry” continues to help out. Before she removes the eyes, she takes the precaution of enclosing the absence—hers, the other person’s? —in a blue bottle suitable for asuntos del dolor. Moreover, the surprising last line depersonalizes the emotion she feels by associating it not with herself but with the sea: Así es el odio frente al mar. Indeed, the poem’s title affirms it’s an asunto del mar, a matter of the sea. The sea is an ambiguous but often ominous presence in these poems: it can suggest the unstable threatening vicissitudes of life, of love, even shipwreck and death. In both Honor de la paloma and Permanencia en puerto, the poetic eye can declare the sea non-existent; but here, with her eyes on the table she’s unable to do so and simply dreams of absenting herself physically from the bench, her companion, and the sea. [3]

Ceguera

The notion of ceguera in opposition to ojos recurs and is itself complex. So let’s glance at a long confessional prose poem dedicated to it, Ceguera. The poem is accompanied by a photo of a misty wood with indistinct and straggly trees that recalls the confused lines of rigging in the photo for Permanencia en puerto. But here the poet praises her ceguera: Una ceguera a la que, por terrible y avariciosa, / por frívola e inhumana, por viscosa y sombría, /amo. The unexpected amo gets a verse to itself. Then she reels off a list of horrors that she “sends” to her ceguera, like /los ultrajes que comete la iglesia católica, / esa mujer rohingya cuya bebé /fue arrojada viva a la hoguera, /…/ But she also sends to her ceguera places of beauty that cause her pain: montañas cubiertas de neblina, / playas donde el delfín anida enamorado, /… / Her ceguera is refuge against suffering whatever its source. It is like a bubbling cauldron: En mi ceguera se queda todo lo arrojado, /fermentándose y sudando aromas /que parecen los esperados besos de mi madre muerta/ y que se posan sobre todo lo suscrito y lo olvidado, / como un brebaje inédito para el ojo que no mira. / At poem’s end, she admits: Hay una parte de mí, arrogante y suicida, / que también envío a mi ceguera, / que es veleidosa e inconstante. This hurtful self-knowledge too is relegated to ceguera. In short, ceguera is where she “sends” and controls the pain she feels at both life’s horrors and its beauties and her own inconstant and violent impulses without denying them. Thus, her ceguera is as relative as her ojo; they are two sides of the same poetic coin.

Sal de mesa

But let’s return to the sea with this multifaceted poem. The underlying idea here seems clear enough: the sea in all its hurtful power is not for casual tourists. The photo that inspires it is of a dark wall with a rectangular opening through which is visible a seascape with a cloudy sky.

Hay quienes

necesitan el marco de una ventana

para poder mirar al mar,

del que huyen descreídamente.

El mar,

intruso impenitente en una isla,

peca de imprudente y les persigue 24/7.

Más que guardián, hermano, detective

o viajero, el mar es dios,

el padre nuestro que estás en el agua,

que todo lo ve y está en todas partes.

Sentados a diestra y siniestra del padre,

los incrédulos admiran

la ventana derramada sobre la mesa,

se sirven con holgura

y se la llevan, mientras arde, a los ojos.

El llanto les recuerda que en otro lugar,

casi al alcance de la mano,

están las ilusiones olvidadas,

esas que nos miran siempre

desde la intemperie que no quiere estar en el paisaje.

The first lines tell of those who need to look at the sea framed by a window, in effect enjoying it tamed. Then, sarcastically and humorously, the poet informs us that an island is no protection from the sea, which is an “impenitent” and imprudent invader that pursues these skeptical travelers of life “24/7”. The sea is not a friendly personage like a guardian or brother or detective but god, our father: the language becomes ironically religious and we observe the “unbelievers” (in the power of the sea) sitting “to the right and left of the father” admiring the window spilled on the table, serving themselves and lifting it to their eyes which burn as if from the sea’s salt (as the poem’s title suggests). There is amazing imaginative density here as the window (and hence the sea’s feared but unsuspected power) is “spilled” like salt (hence the poem’s title) onto the table of which they partake and lift to their unsuspecting (and unpoetic) eyes which burn. The last lines give the story’s moral: The pain they feel reminds them of the forgotten illusions that are always there observing us but beyond comfortable landscapes.

Now, the reference in this poem to god the father as an image for the sea, however amusingly, leads me to a consideration of the various and, I think, significant references to father and especially mother in this poemario, and also in this long following poem.

Soledad de la sal

The photo is of a beach cluttered with driftwood, coconuts and pieces of plastic; in the middle distance there is the indistinct figure of what seems to be an old woman sitting on a chair shielding herself with a bright blue umbrella, while at her feet is a small dog. Beyond the broad beach, in the upper part of the photo, we see the edge of the sea with breaking surf, and above that a bluish sky far lighter in color than the umbrella, as if we’re seeing it through a haze of Sahara dust.

I

Ella sabe de la soledad del mar,

de su temperamento taciturno y de las dolidas carcajadas

con que muestra su blanca dentadura.

Sabe de sus sacrificios y de su incertidumbre,

de su mansedumbre ocasional

y de toda la mitología que su sal alberga.

Conoce su parto paternal, su afán de buen proveedor,

el ahinco que pone en cuidar sin que le cuiden;

que duerme mientras viaja, quieto y profundido.

Sabe (ella más que nadie, que ha parido peces,

que ha amamantado hijos que no son suyos,

que ha tirado redes a los pescadores),

sabe, repito, que su agua deja sediento

al perro que lame sus pies.

Aún así, ella lo mira con deseo, con gratitud,

y le obsequia –pan de pan, frutos remordidos-

los escombros que él mismo ha cocinado.

II

Ella también sabe de la soledad de su perro,

de sus gemidos nocturnos en busca de su madre,

de sus ladridos para protegerla y de los blancos colmillos

que la enfrentan cuando la sal de sus ojos cae al piso de tierra.

El mar no sabe de estas soledades.

Por eso viene todos los días

con su sombrilla azul –cielo inerte y sin lluvia,

cielo sin desembocadura de río –

y con su galgo venido a menos

a que la vea, a que la mire,

a que se la goce, así, veraniega y sobrepeso,

risueña, más negra que nunca, sazonada,

hasta se dé cuenta que ella es su hermana,

su espejo,

su madre,

su soledad.

Y que la reclame a ver si, por fin,

llegan al entendimiento a que están destinados.

In the first section of this poem, the old lady on the beach paints us a portrait of the sea as a father who suffers solitude and has other “paternal” characteristics: he’s taciturn; is given to bursts of laughter revealing his white teeth; is capable of sacrifice, uncertainty and occasional meekness; is a good provider without the need to be provided for; and that he sleeps while he travels in his quiet depths. But despite her sympathy for him, even desire and gratitude—since after all she herself has parido peces, nursed children not her own and tossed nets to the fishermen—she knows his salty water cannot slake the thirst of the dog at her feet. In the second section of the poem, it’s the mother who is the center: the old lady also knows of her dog’s solitude, which is different from the sea’s. The dog whines at night for his mother, which is why the old lady comes every day, with her blue umbrella, so that this hound who has fallen on hard times can see her, look at her, enjoy her as she is and realize she is his sister, mirror, mother, solitude and, finally, reclaim her so that at last they can achieve their destined understanding.

What can we conclude about this curious old lady who yearns for the dog to see her as his mother? The old woman comes every day to the beach to try to overcome the solitude of the dog who yearns for his own mother. We might say she has poetic power implicit in the first stanza (she has parido peces) and more explicit in the second because of her blue umbrella which recalls the pigeon’s blue mooring buoy, his trozo de cielo in Honor de la paloma; but though the blue umbrella’s power is limited—it’s a cielo inerte y sin lluvia—it enables her to confront and complement the fatherly sea which has no awareness of the solitude of the old dog—su galgo venido a menos. She hopes that eventually the dog will use his own poetic power to look at her, to see her, to enjoy her as she is, realize their family ties, she as sister, mother; and demand their destined understanding. But why should the old lady expect so much of this mutt? I see a couple of possibilities. First, the old woman wants to transfer to the dog her own transformative poetic capacity so that the dog who is whining for his mother can satisfy his longing by coming to see in her a mother. A second more speculative interpretation is that the poet recapitulates here a distancing from her own mother that might have occurred in life. In that case, this dog is a stand-in for the poet herself who in other poems portrays dogs (or “mascots”) with tenderness. In this view, she projects on the old lady a desperate desire for the dog to see her as a mother and as she really is, physical and personality quirks and all. In other poems, the poet longs for the kisses of a mother who has died: In Ceguera, she speaks of los esperados besos de mi madre muerte, and in La caída de la luna and the brief and musical Unción de los metales she relates “kisses” to dying. In all these poems, the mother is both distant yet essential to the poet.

Los paseos de la Virgen

Now, what about the intriguing female figure in this poem? The Virgin of the title seems to be a young girl. Although she interacts with some angels, this is not the Christian cosmos. The photo is of a vast sky dotted with a profusion of small reddish clouds, perhaps taken at sunset. The poem informs us that Virgin has been walking on the sky setting fire to it with her zapatos ligeros. We see here the poetic power of feet and footsteps. We looked briefly at this poem in connection with the not wholly defeated poetic power of the homeless bum’s foot and shoe in Nike, who will never win a race and be crowned with laurel; but in this case the Virgin’s shoes and footsteps are victorious in the beauty they create.

But the poem also has drama: some angels have been waiting for the Virgin to stop walking so they can put out the blaze, and are annoyed because they have to keep waiting while she continues walking and sowing fire. The poem concludes: Los ángeles no están contentos/ y le ordenan: “Termina el decorado, / que tenemos que trabajar el mar”. / La Virgen, entonces, se asusta/y pone el cielo a llorar. Who then is this Virgin, and who the angels? In my view, as in Sal de mesa the poet employs traditional religious imagery, in this case the Virgin, to clothe the story in myth. The angels, agents of the sea, of god, order her (in direct quotes) to finish with the frivolous “adornment” since they have serious work to do below, with the sea. She is frightened and cries, that is, creates rain. She is like a young girl reprimanded by agents of her father. The sweet short poem seems to me to have different levels. It hints that the female principle is behind the world’s beauty and its restorative rain. It suggests how poetry is often not taken seriously but considered mere “decoration”. And it admits that while poetic language is a bulwark against the menacing seas of “real” life, it is also a fragile one.

Why is poetic language fragile? It’s because it is an effort to achieve the impossible, to unite heaven and earth, luz y sombra. That I believe is why our poet obsesses with language and writing, especially in poems towards the end of her poemario. We saw that in the conclusion to Crucigrama, the “protagonist” avoids language (even though the poem itself obviously does not): El damero expone sus opciones, / sombras y luz, / y la figura, alada, flota sin tocar /el lenguaje, que es también abismo, ceguera. This last line suggests that to use language is to fall into a sort of poetic blindness. We have seen that ceguera is the partially anesthetized region of the poet’s being where she “sends” the experience of intolerable pain and equally insupportable experiences of beauty untransformed by her poetic eye: En mi ceguera se queda todo lo arrojado, / … como un brebaje inédito para el ojo que no mira.

La soledad de la selva

But what happens if the eye does look: can there arise a poem that is somehow free of words that blind? There is a sort of answer to that question in La soledad de la selva, the lovely short poem that follows Ceguera. Whereas the photo that accompanies the latter is of a foggy wood, the photo for La soledad en la selva is of a green grove with some brightly-lit leafy branches in the center. The poem describes an idyllic Eden which words would only undermine: La soledad es algo bueno: / hace la luz estallar y un ojo la mira desde lejos. … No hay espejos, no hay ventanas / ni sermones de la Tierra para exacerbarse en palabras. / Solo la luz, de arriba o de abajo, /como si fuera dios, como si fuera selva, / como si fuera algo bueno, iluminando sus criaturas. So words only “exacerbate” our evasion of life’s horrors as do devices like mirrors, windows and sermons. Here, in this paradisiacal grove, words are unnecessary for there is no shadow, only light. But of course the irony is that they are necessary, for this wordless grove of light is itself a poem made of words. But true to her poetic moral code, as it were, the poet wants to make clear that this is poetry, not heaven, and that we need to be aware of it. Hence, she tells us at the outset that there is “un ojo que mira desde lejos”, and reminds us at the end that her vision is not reality by repeating three times the phrase, “como si fuera”. It’s all a game; it’s “as if” it was so. She has it both ways: she frees herself to use words to create a place of beauty where words are unnecessary.

Aljaba para lanzar la pluma

This poem, which is on the facing page of the poemario, continues the poet’s meditation on writing from a quite different perspective: as the title suggests, it compares the pen to a lance. The picture accompanying the poem is striking: an aerial photo of a vast green forest into which extends an elongated black lake in the shape of a fountain pen, or perhaps a lance. The first stanza refers us back to the previous poem, La soledad en la selva: Mirar la lanza, / su herida en el costado / de nuestras selvas. So the pen is a lance that “wounds” the idyllic poetic selva like that which penetrated the side of the dying Jesus. The poem consists of five short three-line stanzas staggered downward on the page as if mimicking the flight of the lance before coming to rest with this last stanza: Y que el pájaro / vea, desde su árbol, / morir la lanza. Here’s my interpretation: the flight trajectory is downwards, like that of the thrown lance or the pen landing on paper and thus wounding the selva with words; it appears to represent the fatal collision of poetic vision with the earthly reality of language. Well, perhaps not. Poetry comes to the rescue. The poem’s very title subordinates the lance to the pen. And its focus is not on the death of the lance but its trajectory, its flight, the movement between sky and earth, recalling the suspended figura protagonist of Crucigrama, the moment of pure poetic freedom before writing, like the stroll of the Virgin across the sky. And what dies is the lance that wounds, not the pen. Finally, the poem is bookended by poetic insulation: it is the poetic eye that launches the lance/pen and it’s the bird, poetry’s agent as it were, that sees its death. The lance is giving way to the pen.

Fogón con veladuras

In this prose poem which follows, the poet continues her virtuoso meditation on writing by comparing it not to a pen but to ink, as the title suggests. The photo is of the darkened silhouettes of two women inside a rustic building cooking over a bright wood fire what are no doubt typical specialties like bacalaítos; in the window behind them one sees palm trees, indicating this is near the sea. As in the two previous poems, it is the poetic eye that is the subtle protagonist: Hablemos de esa tinta con la que podemos comenzar a escribir en nuestros ojos, que no paran de mirar. Hablemos de su infantil rasgadura en los pulmones, de su impuesto parpadeo. We’re in the realm of pre-writing, poetic vision. In a few lines we learn that the ink is the smoke of the fogón. The poet’s ambivalence to writing appears in the second line: the smoke/ink can affect our lungs, our breath of life, and make our eyes blink. But her ambivalence extends beyond writing to life itself; here’s the second half of the poem:

En algunos lugares de mi país, el humo es tintura de homicidios, de tortura, de delitos juveniles, de locura fermentada; y hombres y mujeres, como caballería ancestral en rojos carruajes, se lanzan valientes –fundiendo como lanzas su demencia- a exterminar sus raíces.

En algunos fogones de mi país, el humo es señal de alimento y es asunto de domingos. De unas manos –blancas o negras, mulatas o blanquecinas, viejas, recientes o que maduran, pero siempre de mujeres – que surgen, muy cerquita del mar, para ofrendar los deliciosos manjares de Ochún y esa tinta que vuela con la que podemos escribir si la atrapamos en el aire.

Solo así.

Y si los orishas lo permiten.

On the one hand, the smoke/ink in some places of her country signifies brutal violence—notice the use of lance as both noun and verb—and the insane effort to exterminate or deny one’s own roots. She herself is implicated in it. Recall the poem which appears a couple of pages earlier, Ceguera: / … Hay una parte de mí, arrogante y suicida, / que también envío a mi ceguera, /. And her comparison of these violent men and women to caballería ancestral en rojos carruajes casts dark shadows on her otherwise basically positive imagery of horses (see discussion below of the last two poems of the poemario) and of ancestors (in Luz Oriental, writing of people drowned at sea, she tells how Los pájaros, nuestros ilusionados ancestros, /acuden a rescatarlos.)

But on the other hand, the smoke of the fogones signals nourishment at the hands of women both black and white serving the delicacies of the god of Santeria, Ochún, as well as the floating smoke/ink with which we can write if “we catch it in the air” and if—humorously—the orishas permit it. This prose poem of course is about much more than the poet’s wrestling with writing; it’s a paean to Puerto Rico, to its customs, to women especially the humbler ones, and it’s a recognition that the culture is morally ambiguous. Twin streams of humanity and violence course through it, the latter including the rejection of one’s own culture.

These successive poems suggest movement towards a less ambivalent attitude on language. We recall how in Crucigrama its protagonist, the floating figura, avoids choosing between “light” or “shadow” or touching language que es también abismo, ceguera. Similarly, in La soledad de la selva, words can only “exacerbate” the experience of its pure light. However, in Aljaba para lanzar la pluma, the poet is ready to lanzar la pluma even though it “wounds” the selva. Here’s the irony: the written word creates the selva even as it betrays it. Then, in Fogón con veladuras, she concludes that we can write with that smoky ink though we still need to “catch it in the air”.

From language, I want to move now to a final matter: religion which might seem to be a concern of the poet. I think though that the gods and myths that people these pages are simply part of her poetic language, as are Christian concepts like penitencia or the sagrado. “Penitence” results not from sin but exhaustion from life’s struggles, whereas the “sacred” refers to her poetic goal of “uniting heaven and earth”.

One could say there is a sort of animism in these poems: Sidewalks rise up, streets dance; body parts come alive: hands, feet, a neck or an ankle bone, as do diverse things like a padlock, shoes, a bus, a graffito, light and shadow, birds, sea, salt. Things possess an autonomous agency sometimes reflected in the titles: Calistenia de la tiniebla, Soledad de la sal, Don de nube. But like the Christian terms, this curious vitality of things, birds or parts of the body is simply part of the wondrous but strange DNA of these poems.

There may appear to be a broader cosmic drama going on, a Manichean battle between luz and sombra. These two words blaze forth in the poemario as if they were autonomous spiritual entities. But I think it’s ultimately just the reality of life shadowed by death. The poet can darken her narrative ominously, as in Astrágola para una calle: Alguien ha ordenado apagar el sol/ y, aunque piensas que caminas, / entras en la noche como sobras de un misterio. But she can also turn the “struggle” into a game as in Crucigrama: Cuadricular la luz o cuadricular la sombra/ es tarea imposible. La figura lo advierte/ y pone palabras en cada sombra, en cada luz. And she even pokes fun at it in Autoría de sombras: No se habla de la sombra, / como de los muertos en el abismo del olvido. /Se la recoge en bolsas para no mirarla nunca, se la barre ante nuestros pies para que no obstruya el camino, / … /Nadie sale a defenderla. /Ni la luz, / que es tan lingüisuelta.

But then what are we to make of the “mystical” experiences in the poems that end, respectively, the first and second parts of the book? In both, the poet describes intense circular movements explicitly associated with dervishes, members of an Islamic Sufi community who whirl in dance in order to attain an ecstatic trance and union with God. To try to see what this is all about, let’s look at both El tiempo detenido which concludes the first part of the poemario and then the two closely related poems that end the second, La meta and Belleza del azar.

El tiempo detenido

The photo that accompanies the poem is of a rusty scale with its pointer stuck on zero hanging from a ceiling that has a brightly lighted opening. Although the poem begins with a line that bears upon the photo— Pierde su peso la fruta, —it quickly opens into a vertiginous experience: Pierden su gravedad las raíces, / el estómago y sus ansiedades circulares. / Los anillos del árbol se van a viajar, /perdidos su eje y arrancada su canción. / El temporal, incansable derviche, / une sagradamente cielo y tierra /…y todo lo que en medio baila, truena, /todo lo que en medio truena, baila, / y todo lo que en medio gira, muere, / todo lo que en medio muere, gira, /…y danza interminablemente/… / Then, in the poem’s second part, the author questions whether she is the one who should record this singular event: ¿Acaso soy yo la guardiana del tiempo y el tiempo, / tan sujetos ambos a sus espirales, /que tengo que registrar de ambos sus liviandades, /… /todo el agua del mundo me rodea, como isla, / y pierdo peso, / yo que nunca he tenido fe en nada.

El tiempo detenido dramatizes, I think, the birth of a poet. This turbulent poem portrays her surprised discovery of her role in life and indirectly analyzes the experience. First, the phenomenon has a physical basis: that of a hurricane (temporal).[4] All her poems are anchored in the real world, no matter the exotic directions they may take, and this one is no different. Secondly, the powerful swirling storm acquires spiritual force similar to that of whirling dervishes that can “unite heaven and earth”. This is what her poems strive to do. But we notice that this dance is less exhilarating than “interminable”, perhaps because of this exhausting effort to achieve what is impossible. Thirdly, the poet senses a call to record these experiences, that is, to be a poet. Though not religious—she says she has never believed in anything—she is surprised by the “summons” and reluctant to answer it. It’s a call to register the lightness (liviandades) of a world loosened by the spirals from the heavy gravity of earth; losing weight herself, she seems to accept the challenge though retaining her doubts. In this poem, she has recorded the stormy dance of inspiration and creation. If this is religion, it is the religion of poetry.

Let’s turn to the book’s last poems, La meta and Belleza del azar. The latter features a spiritual experience that is also compared to the dervishes’ dance. To understand it, we need to look first at La meta since the protagonists of both poems are “horses” that are “running”. But a notable difference is that in La meta the horse protagonist has a desire to kill the jockey, whereas in Belleza del azar the little horses not only have no such violent impulses but appear to achieve a sort of poetic-spiritual transcendence.[5]

La meta

The striking photo that inspires this little gem of a poem is that of the rough-hewn bark of a tree trunk that could seem to be the face of a horse, a quite imaginative leap.

El caballo, desbocado,

mira la meta con el terror del sueño.

Ha despertado recién

y no sabe si es madera de la cerca que lo encuadra,

del ojo que camina allá, más adelante y solo,

o del bufido de un dios que no conoce

(no tiene aguas para mirarse).

Le fue arrebatado el cuerno que le fuera prometido

para coronarse rey y prodigio;

no ostenta las alas para convertirse en libertador,

halcón o búho venidos a palabras.

Tan solo se siente caballo y galope,

mirada y galope, posibilidad y galope,

aunque esté en tierra detenido.

Desbocarse le hace ilusión.

Detener el carrusel y asesinar al jinete también.

What do we learn about this “horse”? Just awakened, he has little self-knowledge, wondering whether he’s the wood of his enclosure, the creation of an eye, the snort of an unknown god. And he lacks the mythological connection (the horn, the wings) that could free him imaginatively from his earthly restraint. He senses only that he is a horse, a look and a possibility, a galloping; the lines convey the powerful rhythm of the gallop. His dream is to run away, bolt (desbocarse), “stop the carrousel and also kill the jockey”. In my view, the extreme tension between his sense of being a galloping horse and his awareness that he’s stuck in the tree bark, without mythical backup, makes him come unhinged. The title, La meta, meaning goal or finish line, suggests he wants to win, that is, not only win a race but break out of his imagination into reality. In this poetic universe, that is impossible, a dangerous delusion. He imagines himself on a carrousel that he wants to stop and with a jockey he wants to kill. But as we will see in our discussion below of Belleza del azar, a real carrousel’s ongoing spinning is what is life enhancing.

We might note that the violence in this and other poems is at bottom not metaphysical but human in origin. It is the human hand that both strangles and caresses. Violence may simply be part of our nature. Under the diverse pressures life imposes, people can become suicidal or murderous. In the cultures of Indonesia and Malaysia, a person was thought to have run amok when a tiger spirit entered his body and caused him to commit a heinous act. The state of mind of this tree-horse recalls the locura fermentada, the crazed violence of men and women that in Fogón con veladuras the poet compares to a caballeria ancestral en rojos carruajes.

Belleza del azar

This poem that follows La Meta and ends the book features a real carrousel with toy horses and jockeys. Belleza del azar concludes the second part of the poemario, just as El tiempo detenido does the first part. As we have noted, central to both poems is a whirling circular motion likened to the dance of the dervishes and connoting the achievement of mythical power.

The photo is a colorful depiction (red predominates) of a pica, a small carrousel common in small town fairs with figures of horses and their jockeys that whirl around in a game of chance. Throughout, and perhaps more so than in any other poem, Belleza del azar seeks to unite reality with myth, yet as always strives to maintain awareness of their difference. It begins thus: Todo el orbe se reduce /a esa pequeña pista circular /en que el piquero es un dios, dador de bienes, /dios de muchos nombres. So this little turntable acquires cosmic significance, its operator a god who gives out prizes. But then reality breaks back in as the following 22 lines demystify these little circling wooden horses, detailing the many mythical, artistic or historical accomplishments that will never be theirs. Here is a sampling: Los caballos de su reino no han nacido del mar / ni de cabeza de mujer; no han sido nombrados cónsules / … /No estarán en ninguna batalla de Ucello / … /No han sido ni serán montados / por amazona alguna o conquistador de truenos / … / Sueñan el imposible retozo de unos juegos olímpicos / o en lo que podrían ser / si sus patas y sus corazones fueran libres. / Largas distancias siempre en el mismo sitio, / caballo y jinete, fijados, se desconocen:/ It would appear these little wooden horses are no better off than the tree-horse of La meta. Still, this long litany of wonders that never happened to them leaves on the reader’s mental retina a glimmer of possibility, and eases the transition into a sudden transfiguration: /no tienen ninguna pista de su destino, / solo la noción de una mano, la del centauro, /prehistórico y en evolución, / dada a las maravillas del aburrimiento. / Sujetos están a esa mano que rige las galaxias espirales, / móviles como entusiasmados derviches ilusionados, / afanados en su liviandad y su repetición, / serviles a la vileza del azar, que no deja de ser bello.

So why is it that the outcome for these little horses is different from that of the horse of La meta? There are I think various reasons. First of all, they have the notion they are controlled by the hand of a mythical centaur. And so unlike the tree-horse, their imagination is both elevated by myth and restrained by reality, since the centaur’s hand is that of the piquero, a real man. Myth is carefully tied to reality, the more so because the half-man half-horse centaur is prehistórico y en evolución. We may recall the life-affirming pre-historic human hand prints on the wall in Las manos de la cueva. This hand of the piquero-centaur—dada a las maravillas del aburrimiento—brings wonder out of the monotony of existence.

Additionally, and contrary to the tree-horse, these little pica horses have the advantage of being in circular motion, likened to that of entusiasmados derviches ilusionados. And it is anchored in reality, that of the revolving pica. Moreover, and perhaps surprisingly, if we look closely at this line, móviles como entusiasmados derviches ilusionados, we can see that though the horses do share the mobility of the dervishes, that may not really have their enthusiasm and illusion. However imperceptibly, the poem preserves the dividing line between reality and myth.

A final difference with La meta is that here the union of reality and myth is a game. The pica is a game of chance; while it is whirling, no one loses and winning seems possible. In my view, what fascinates Vanessa Droz is the game itself, the movement, the options, the poetic possibilities, not the winning (a deadly illusion as we saw in La meta) and much less the losing which is life’s fatal end-game. But the poetic game does offer a kind of win since it is a bet on seeming to transform reality; or, to change the image, it’s a high-wire performance that appears to suspend gravity. In La soledad de la selva, luz seems to shut down tinieblas without truly doing so: Solo la luz, de arriba o de abajo, /como si fuera dios, como si fuera selva, /como si fuera algo bueno, / iluminando sus criaturas. It’s as if reality were thus. And Indeed, Belleza del azar’s last line abruptly drops the little wooden horses back to the reality that they are merely pawns in a game, though one in which reality and myth have fused sufficiently to create beauty.

I admit to having had difficulty appreciating this last line, serviles a la vileza del azar, que no deja de ser bello: I thought, how can chance (azar) be beautiful? The whole poemario is proof that beauty is not random but the result of inspiration and sweat. Worse, I wondered how can the experience of the little horses be beautiful if they are serviles a la vileza del azar, a humiliating condition? The poet’s final lines are often surprising, but this one seemed to me absurd. But then I noticed the careful phrase, que no deja de ser bello, which might be interpreted thus: while it’s true the horses are serviles a la vileza del azar, it is also true that the poetic transformation they have just been through has made this pathetic reality beautiful. If so then there is no contradiction. But I still found fault with the title itself, Belleza del azar, which appears to claim that chance itself—unmediated by myth—is beautiful. Could it be that the melodious consonant sounds in the title and indeed in this last section of the poem veiled its illogic from the poet herself? Perhaps. Here’s a possible alternative explanation: “Belleza del azar” is in fact a succinct summary of her theory of art and life. Both art and life are on-going games subject to el azar, to chance, but while the game continues we have the opportunity to create beautiful mythical alternatives of our own. Chance places determinism on hold and so gives us our own space.

***

In conclusion, Vanessa Droz has written a subtle, profound and yes—beautiful—poemario that dialogues effectively with the singular photos of Doel Vázquez to create the unique work of art which is Permanencia en puerto.

______________

[1] In these poems the seeing “eye” is crucial. Vanessa Droz has commented that what she likes in the photos of Doel Vázquez Pérez is that he sees what others don’t. Interview by poet Mara Pastor on Radio Universidad, July 17, 2019.

[2] This is but one example of Vanessa’s careful design of this poemario. She likes to “construct” her books as a total work of art, determining insofar as possible the size of the pages, their format, the type of paper, the ink, the colors, the cover; it would be great, she says, to be able to taste the book. In same Interview by poet Mara Pastor on Radio Universidad, July 17, 2019.

[3] In the same interview referred to in the previous notes, Mara Pastor asked Vanessa Droz why she had allowed decades to go by between her early poetic publications and her recent works. Vanessa replied, “Me enamoré”, explaining “nací para escribir poesía”; it’s as if for her love and poetry proved incompatible. Mara commented, “Yo nací para amar”, implying that for her both were possible. Vanessa then reiterated that she had been born to be a poet.

[4] This book was presented to the public a year and a half after Hurricanes Irma and María.

[5] The implicit contrast between these two related “horse” poems recalls that between two earlier “bird” poems, Plegaria del pelicano and Estrategia de la garza. In the first, death awaits a fearful aging pelican who is losing his confidence in flying and finding food, while in the second a heron though also ageing retains that confidence and ability by a poetic “strategy”.