The Body Cannot Lie: Manuel Alum on the Creative Process

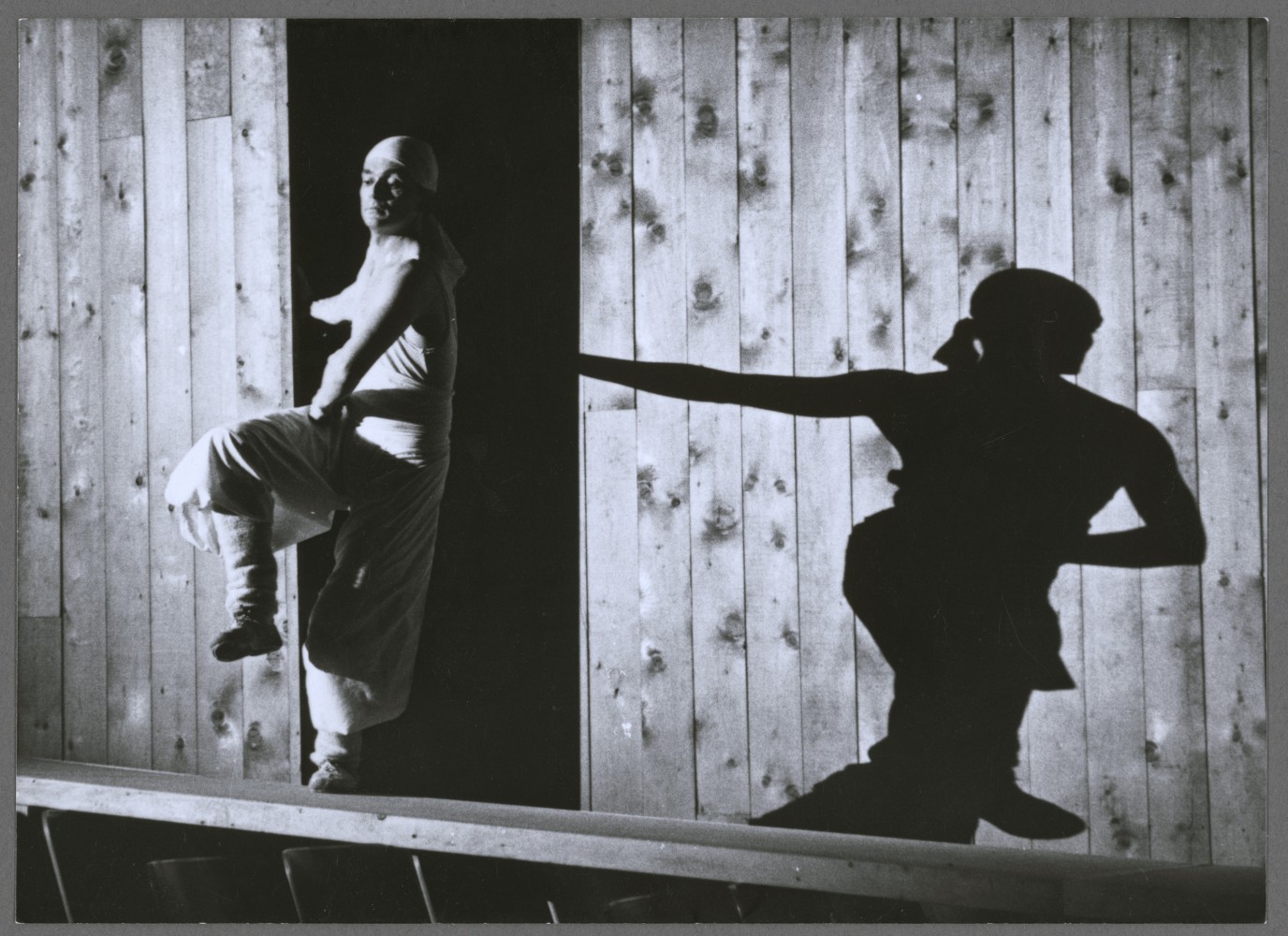

Manuel Alum fotografiado por Philip Trager, 1989.

Manuel Alum (1943-1993) nació en Arecibo, Puerto Rico, y fue residente de Nueva York la mayor parte de su vida. Desarrolló su prestigiosa trayectoria como bailarín y coreógrafo en los Estados Unidos, con significativas presentaciones en Asia. Visitó Puerto Rico en dos ocasiones: en 1984, invitado por Francis Schwartz y Actividades Culturales para presentar su solo Made in Japan en el Teatro de la Universidad de Puerto Rico y ofrecer una conferencia ilustrada en el Teatro de la UPR Humacao; y en 1985, invitado por Gilda Navarra y Taller de Histriones para la creación de la pieza de grupo Al pan, pan… en el Teatro de la UPR.

El archivo artístico de Alum se conserva en la colección del New York Public Library for the Performing Arts en Lincoln Center; asimismo, el Archivo de la Danza de la Biblioteca Lázaro de la UPR custodia una selección de sus documentos, curada por Oscar Mestey Villamil. En 1987, Alum fue entrevistado por la actriz, escritora y activista por la salud Marguerite Oerlemans Bunn, británica radicada en Nueva York. La grabación de la entrevista permaneció inédita en los archivos de Oerlemans Bunn, quien falleció en 2004. Esta es su primera publicación, transcrita (de la cinta original provista por la hija de la escritora) y editada por Nelson Rivera.

Manuel Alum, Jacob’s Pillow 1981.

Manuel Alum Dance Studio, New York, July 1, 1987

Marguerite Oerlemans Bunn: Manuel, how come you decided to be a performance artist and a dancer?

Manuel Alum: I never thought of myself as a dancer, when I was young, or anything like that. I did think of myself as a painter, my first love was painting. I liked the theatre but never thought of myself as a performing artist. I was very physical as a child and always sort of liked dancing and had seen a lot of dance. My father had a hotel, so in the casino, dancers like Alicia Alonso would be rehearsing. They left an impression on me. I still never thought of myself as a dancer but I liked watching dancing. Also, as a child I had a room next door to a building, where I could hear a dance group, Spanish dancers. There were some ballet classes also going on in the studio. I didn’t see them, but heard them, so by hearing them, it stimulated my imagination, to think about dance and movement. I think that also left some grains inside of me, thinking about, some seeds. But it was not until I was a painter, already going to the [School of the] Art Institute of Chicago that I found out about modern dance. I saw Martha Graham, [Jose] Limon, Sybil Shearer. Seeing Sybil Shearer made me desire to go try dance seriously. I had a need, I shifted from my painting into the body, to movement, thinking that I would invent something new, some other new way of dancing. I came to New York and found out a lot of people had been ahead of me. It would seem like that was yesterday, and here I am, still doing the same thing. It just happened, I had a facility for dancing and I was always physical but never thought of it seriously, as a serious act to get my whole life into.

MOB: When you came to New York, who did you go to?

MA: I went to Martha Graham, at that time was the kind of place to go. It was very valuable for me. She asked me to be in her company, she was already working with me, but somehow I felt that the technique did not accomplish a lot, it was not the place for me to grow. I wanted to choreograph right away and could not at that time, they did not let the dancers choreograph. And here is a company where the star was in her sixties or seventies and the chorus was in the fifties and I was only nineteen. So it was hard for me to get in there. And I thought, “I will probably spend here some twenty-five years and still be in the background”. So, it was not for me. I made the decision not to return. I wrote her a letter and decided to start choreographing and immediately I choreographed, right after that.

MOB: Did you make your own company then or…?

MA: I worked with Paul Sanasardo, who offered me the space to make my mistakes. He liked my ideas for dances and I choreographed and he liked my dances. I began working with him as a principal dancer and assistant director of his company, which was a good place for me to learn and to make mistakes and all that. I was choreographing three months after I met him, had my first New York season.

MOB: So, basically, you were on your own from the beginning.

MA: I began forming my own vocabulary; my initial pieces were the beginnings of my vocabulary. Three months after I met Sanasardo I did my first dances, so there was already a very strong need in me.

MOB: And also, specifically thinking about dancing.

MA: Yes, nothing around satisfied me, so I had to do my own.

MOB: Did your family support you in this?

MA: Not really, no, they thought that was crazy. Now they’re kind of proud. Somehow, they did not quite understand why I chose this kind of life. They got used to the idea, but they did not understand it, in the beginning.

MOB: There aren’t any other performers in your family?

MA: No, no. My father’s a wonderful dancer, you know, tangos and ballroom dancing, he imitated Fred Astaire… He’s quite an agile mover.

MOB: So, as a child, you didn’t dance at all?

MA: Well, not seriously, I mean, I liked to dance. I remember my aunt, she used to pick me up and we would dance together in the casino, you know, I was like ten or twelve years old, very little. I choreographed in school just because I thought that I could do it and choreographed a lot for my sister, when we were young. We used to do crazy things. There’s a certain religiosity in my work and, as a child, we had that kind of a thing. We had a platform in the fifth floor of the casino where at two o’clock in the morning my sister and I used to go. She used to play the piano, I used to dance, and I used to choreograph for her, you know, not thinking I knew what I was doing, just doing what I liked to do. But the thing was that that platform was forbidden to go on, because it was five stories high, pretty dangerous, but we risked that, we used to pray that we would go on and danced and, after the show, we prayed that we didn’t fall. It’s the same today, when you go on stage you have no idea what’s going to hit you, what’s going to happen, whether your muscles are going to respond or whether you’re going to break your neck. So, it’s a little bit like those performances when I was little, actually.

MOB: But your sense of religiosity is very living.

MA: Somehow, it’s still there. It’s not a conscious thing. It is something that, if you are faithful to yourself, comes out.

MOB: How do you get your ideas for your pieces?

MA: Oh, I don’t… I think, I look around, I mean, I don’t plan them. If I think it’s a good idea, I do it. Often, it’s the music. Sometimes, a situation. Sometimes, it’s just growing around me.

MOB: Are you very observant when you’re out in the world?

MA: Well, just being alive today and being aware of what’s going on, there’s a lot of things that are going on that you either want to criticize or you want to talk about, or you want to make new comments about it. It all depends. Some pieces come out of a strong need.

MOB: From an individual sense of…

MA: That’s right, yes.

MOB: Does one work lead to another, sometimes?

MA: Yes, sometimes there’re some works I have choreographic interests that develop, that I want to continue in that direction. There are certain pieces where it is important for certain choreographic developments.

MOB: Do your ideas come to you as choreographic needs?

MA: Oh, it depends, each piece I do I try to experiment and try to find some choreographic challenge or something that I want to feel is mine or comes from my own way of thinking. Then, there are these other elements that are beyond me, my own chemistry, my own background. But there are a lot of conscious things that I try to work and deal with, because I do still believe in the power of the body speaking. Usually, I have to find something that interests, that challenges me. Something that I can click into and that I feel is important or worth taking a chance, experimenting and risking something.

MOB: When you’re thinking about new pieces, do you see the movement in your mind? For example, there was a movement in one of the pieces where the dancers were all lined in their places and rotating their arms…

MA: Yes, I visualize sometimes, especially with groups. I like to experiment and do groupings that are alive, a group of people moving like one person with many arms and many legs, or a “feather effect”, which I think is what you were referring to.

MOB: That’s right, yes.

MA: That type of thing. Or I see a certain kind of weight, a group of people rendering weight, too, or lightness, depending on what I’m experimenting on. This particular piece [Monte], I was dealing with inclinations, not a flat floor but an inclination, like a monte, like a hill, rather than just a flat floor, so I knew there were a lot of things that came out of that way of thinking. Different things that got through my mind guided me and I listened to my instincts.

MOB: So you think partially in visuals, dancing effects?

MA: Actually, yes, I visualize a lot when I work. There are so many things nowadays, that’s just one part. There’s also the music. Monte is my first Mozart piece. The music provoked certain things in me and I tried to provoke certain things with the dance, to people, so that it is not just in response to one level but to many levels, spiritually or physically. But another thing happens today: it’s the economics. There’s little money and I have to have all my dancers together, so that takes a great deal, that dictates to you, whether you want it or not. You have to use your knowledge to make the most of the situation in an interesting way and yet put back what you had in mind originally. Most of the time I don’t have all the dancers together, not because I want it, but because they have to be doing their job at a restaurant or, you know. So, a lot of it was accidental, in that sense which, I hate to say it, you just have to. A lot of the dancing today is because of that. There’s very little money and dancers have to get paid, so you have to do with what you have. And that dictates the work. But you have to be smart enough to know and predict that and try to make the most of the situation, to your satisfaction. Because it is designed by mind, but there’re so many open ends because of this lack of funding that it, unfortunately, I hate to say it, I never thought I would ever say this, but a lot of it in this process has to do because of the scheduling of dancers. Especially in a group piece. If it’s just a duet or trio it’s easier than when you have nine or eight dancers, it’s hard, it’s very hard.

MOB: You mentioned before the formulation of your own dance vocabulary. Are you thinking of that when you are forming…?

MA: Well, yes, I fall back and use what things I have, it happens like that. It’s a modern vocabulary. I choose to use those things to communicate physically, kinetically. I have developed certain things that work for me and I’ve thrown away a lot of things that I’ve tried and don’t work.

MOB: And that’s your personal dance vocabulary.

MA: That’s right. It usually comes from my body, but it also comes from people with whom I’ve worked for a long time, people that I have trained, people who have been around me. It’s a relation with them, also, not just my body movement. With Felice [Norton], for example, with whom I have worked for twenty-one years. I watch her and not only her, I watch all the dancers.

MOB: When you are working on a piece and developing it, what is your style? Very concentrated, you get here every day?

MA: We work pretty hard, yes, because if I had all the dancers all the time here with me, we would have a different tempo. It changes because you don’t always have the same people. That has been a difficulty experienced in the last three or four years. Since I came back from Japan, actually. The whole dance scene in New York has changed and it has less to do with the creative process, unfortunately. It has much to do with the political and money.

MOB: So, you develop your dances more when you are actually working with your dancers, than in your mind.

MA: Well, my mind is always thinking when I’m not here and when we are working, the process is…

MOB: The working out.

MA: Working with the dancers is when things start happening, and gelling. I mean, I don’t wait to “be inspired”, I just work, let things happen.

MOB: And if you get stuck?

MA: Oh, we do get stuck.

MOB: What do you do?

MA: We try, either to put it aside or try to work out why we’re getting stuck. If it’s worth something, I’ll pursue it; if it isn’t, I just dismiss it. Sometimes it’s good to just start cutting.

MOB: If you put it aside sometimes, do you suddenly get an idea that helps you to see how you could work it out?

MA: Sometimes I’ll put it aside for a while and then you find a place where to put it in the dance. Sometimes, I’ve found some wonderful material but it was not the right place nor the right time, like in this last piece, there’s a lot of material that was cut, to edit it out. I finally did and it was the best decision. But I will say that I would put it in another piece or something.

MOB: Does it help you to leave things to rest for a while and then come back to it sometimes, work out a problem or if you don’t know where to go next, how to develop something?

MA: It depends, sometimes I had put it aside and then it came handy later on. Sometimes it just was not right. I was just going too far off from my original intention for the right thing for that particular dance. So for the dance to have its own integrity, it tells you whether it’s right or wrong and you have to listen to it, no matter how much you like the material. I do have some material that I like very much but I can’t put it in because it tells me it’s wrong to put it there. You open your antennas and you start listening because at the end it tells you more than you tell it.

MOB: You ever dream about your work?

MA: Not about the dance itself, no, but I make dances out of my dreams. I had a series of dreams that I translate into dance movements and use it for the kinetic possibilities that the dreams open up for me, not so much to translate an exact dream but just to get the feeling of it. The body can do a lot of that, choreographically. I have this whole technique of when I have a dream just trying to stay up and write about them before I lose them.

MOB: But you don’t get solutions to problems in dreams or work out a dance.

MA: No, not solutions. Sometimes I have images that come from my dreams, but the actual choreography and working is what makes the dance, yes, the dealing, working with it, that is what makes it happen.

MOB: And sometimes, when you’re doing unrelated things, going about ordinary activities of daily life, do you sometimes get insights about the dance or movement?

MA: Absolutely, dance and movement, and sometimes it’s even about just living. You put that knowledge into your work and things are very clear.

MOB: A sudden flash of insight.

MA: Right. And you go, “oh yes, that’s what I should do”.

MOB: How do you explain that? Do you think that something has been unconsciously working?

MA: Oh, yes, I believe the mind is always working. When you are not working, your mind is working. I’m certainly choreographing when I am not choreographing.

MOB: Things come to the surface…

MA: They come to the surface and then I use it, but you have to be in touch and have to be sensitive to yourself and try to use those things.

MOB: Do you develop that as a life school, sometimes?

MA: I think you practice and then you try to be open and sensitive to it because you know that these are good accidents, with thoughts that come to your mind, so you listen to them, rather than having a formula. I don’t believe in just having a formula. I use as much as I can and try to make the dances rich in every level, but they also should be solid, structurally and all that, so I try to develop my craft that way. There’s so much to get from by just living and being aware of what’s going on that sometimes even if I’m just cleaning the table, I have a thought about movement or a connection of “that’s how it should be done” and I try to make it as interesting as possible, for sure.

MOB: A number of artists talk about how you suddenly see something very clearly and sometimes you have no explanation of why this insight just comes…

MA: It doesn’t happen that often, it’s not like “ah, that’s it”, doesn’t always happen like that. But there are certain things that just gel in my mind and I see what I’m doing and how it should connect. And that’s nice, because then it all falls into place.

MOB: And then, the verifications of whether that’s workable you would do with your dancers, working out…

MA: It happens right there in the actual work, those few seconds when you’re trying something that did not work the second before. You dive in yourself with your instinct, your thinking, you know that clear pattern. It’s one of those wonderful moments when you’re not working in the studio and then you just have this idea and you try it and have to channel the dancers into that way of thinking and then you go just right. In dancing, it’s a little bit different and more difficult, I think, because you have people around and if they don’t understand where you’re coming from, it’s too fragile a thing. Especially if you have eight or nine people in one movement in one second, it’s very hard for the mind to focus right into that. In painting, it’s just you and the canvas. Often, with a lot of people you are more lonely than when you’re with the canvas because they don’t understand, they’re just doing steps, so it’s important that they understand where you’re coming from and then they can get into your head, so that thing that crosses, is more to the point.

MOB: What is effect on your work of your own emotional state of mind?

MA: Oh, I just get happy when I do something I feel “ah!”. I get excited, that’s all there is, that’s the only satisfaction I get when I do something “that’s what I wanted to say”.

MOB: But if you are feeling personally depressed, anxious…

MA: The best thing is work. Absolutely. I wish I felt good all the time, but it doesn’t always work like that. But I work. Sometimes when I’m feeling lousy I get some very good work out of myself, so it all depends on the piece and what the whole work is. It’s not like I work abstractly all the time, you know, each piece has a certain focus, each dance has an integrity of its own.

MOB: How long do you work on a piece like Monte?

MA: Monte has taken a long time, but I think the reason is not because of the creative process, but because of the lack of money.

MOB: The economics.

MA: The economics, the lack of having all the dancers together and me waiting around. I have more time waiting around than the actual going into work, like I like.

MOB: Is that frustrating?

MA: It’s very frustrating because you have to be careful that your interest doesn’t die.

MOB: You get angry.

MA: I get angry, that’s ok because that’s all part of it. But it clouds what you are trying to do. This took quite a while because of not having all the dancers at the right time. It’s unfortunate, but everybody suffers this, every company, even companies that have a lot of money…

MOB: When you say “quite a while”, you mean months?

MA: Months, yes, about four months.

MOB: But what about your own, the two pieces, for example, that you did, your personal pieces?

MA: The solos, sometimes, come very fast. The idea for the first solo came very, very fast. It’s a prayer and with the structure I wanted to do what the voices are doing by exploring different rhythms in the body. The other solo is a political statement, I wanted to do something with the music of Davilita, so that sort of fell into place very quickly. But then, it’s easier with me. I just deal with myself.

MOB: How do you know when a piece is finished?

MA: Well, a piece is never really finished. The skeleton is there, there’s the beginning to the end, but then it’s going to mature, the content has to come out of your skin and that happens by doing it a lot. Monte is not really finished. Monte is just now beginning to mature, but it takes a while. It takes many performances, I think all dances do, they’re just not finished. They just have to hold on the right place.

MOB: But you have a sense of when you’ve done enough, when it just starts to grow…

MA: Oh yes, and that’s when it’s ready to open. Right now, it just needs to mature. You have to finish the structure and that’s in your mind, your thinking; then by seeing it, the more you do it, you know that it gels, focus, and it’s more clear kinetically. I like the dance to speak to me. Not only in technical craftsmanship but in what the dance has around it. What it says. Which is why I think that true communication that is kinetic is just provoking other things other than what you’re just seeing, the skeleton or its structure. You’ve got to see something else and that something else which we cannot put our hands in is when it matures. When it is already freeing itself.

MOB: The structure and the performers and you.

MA: All the things are gelling, everything, when all the dancers are really connecting. The whole dance has a very clear, overall, look to it. Then, it’s mature.

MOB: Is there a lot of emotion attached throughout to you when you see one of the pieces which you developed and then performed again and again?

MA: Well, I have to divorce myself from them. The more I see that happen, the more I have to get away from it. By doing that, sometimes I see pieces that I did twenty years ago and I go, “how did I do that?” It took twenty years to get to that point. You know, like Palomas, of which you only saw excerpts of the whole piece. It’s a very strong work, women talking about life. It still works for me and I did it twenty years ago and don’t know how I did it. But I was guided by my instincts. I was very close to them and my feelings about the life. I had a concept, then some choreographic ideas and I just put all that together and it came out as Palomas. What surprises me is that twenty years later what I see is not any of the separate elements but the whole synergy, of everything, it comes across very clearly.

MOB: Why do you say that you have to divorce yourself?

MA: Because there’s nothing you can do about it if it’s done; you would harm it if you would completely change it.

MOB: But emotionally you’re still…

MA: Oh, emotionally I’m still with it but still have to…

MOB: Let it…

MA: Let it take over.

MOB: Do you show your dances to your friends before you perform them?

MA: Not so much, no. Just started to do a showing to get money, so it’s like a performance and that makes it more objective. I’ll try to do a series of showings this year, works in progress, just to raise some funds.

MOB: But not to get feedback…

MA: No, although I sense people seeing it, even before they say anything. Ideally, we would like to tour outside of New York and smaller houses. That’s what big concert people do; unfortunately, we have a New York season ready to open but I’m doing this for myself, I’m not doing it to compete with anybody, it’s just for my own growth.

MOB: Apart from dancing in the pieces, do your dancers contribute other thoughts, emotions, or suggestions…?

MA: My dancers? Not this company, no. Pretty much, they help solve technical problems, like in groups, ensemble groups, you know, with the counting and the precision. They sometimes come up with their own ideas about how to get to what I want, because Monte is a very complex work, choreographically, and they all have to be very tight, very careful, it could be very dangerous if not. So in things like that they help.

MOB: When the movement is very fast…

MA: Yes, it’s very difficult, very precise and dangerous. They are doing it and I’m sitting watching directing, they have another sense. As a dancer, I remember that my body has a certain knowledge built in my head, so I trust what the dancers say.

MOB: What is, being a performer, a choreographer and dancer, the effect that it has had on you and your relationship to society, the constraints on your personal life, how has it affected you being a performer who dances?

MA: My affective life? Well, there’s no time for it, the work is very demanding.

MOB: Yes, you’ve said earlier that’s all there is.

MA: It consumes you, it takes all your time, even when I’m trying to forget about the studio and dealing with something about the studio. When you are choreographing, you choreograph at all hours, at all times and I don’t know how to do it any other way. I would like to just punch in and punch out. But it’s not that kind of a job. It is not a job. Of course, you try to be human and keep up with the human aspects of living, but… It takes a lot of your time, it really does. Then you see the rewards so it’s ok, I like that. I think it’s better for me I am not a domestic person, so I’m not complaining.

MOB: So, socializing is not an action for you…?

MA: When I’m choreographing it’s very hard for me to go out because, first of all, I don’t have the time. I mean, I’d do just to relax, go eat out or something like that, or see some friends, but I feel that it’s best to be quiet so I can let my mind continue working.

MOB: Do you socialize mainly with other people in the performing field, other dancers?

MA: Oh, it depends. Mostly people in the arts, because of my work. But I’m very curious about many other people. I know many dancers, we’re friends but we don’t socialize. There’s so many things that I’m curious about in life, so I have many friends that are not in the same field.

MOB: All those contacts, social interactions, they all come back to informing and enriching your dance.

MA: Every kind of information I get, including the television, stimulate you to think about what you are trying to do.

MOB: I was interested in your description of Monte as being a spiritual journey. Is the spiritual an idea that comes to you?

MA: Well, first of all, I wanted to do a Mozart piece. I listen to Mozart always as more like being in a mountain, to me. There are certain truths that are universal, that people all share no matter where they’re from, what country, or what they do. There’s a spirituality that a mountain has, the spiral ascending. I also had read about that from Jetsun Milarepa, the eleventh-century philosopher, who spoke a great deal about this spiral ascending. [Constantin] Brancusi also spoke a great deal about that. So, you know, I’ve always been attracted to that. It is spiritual because it shows people dealing and living and working and having deep joy and having sadness, experiencing all the odd experiences. Putting that together and then trying to make a community of it was an interesting thing and I felt the music of Mozart was perfect for what I had in mind. Actually, I think my early dances had the seeds and I’m just right now growing, blossoming those early seeds. So there is a signature in all the more than fifty pieces that I have done, they all have the same kind of, as I say, religiosity or…

MOB: Or connecting.

MA: That’s right. Monte recalls Nightbloom, which is very much what this piece is doing but in a much larger scope, Nightbloom is a quartet. They’re completely different pieces, completely different worlds, but they’ve basically the same thread, the same fragility about people and moving.

MOB: And the aspirations.

MA: That’s right, at different levels, spiritually. So Monte to me means a bigger, a full, a richer Nightbloom, that I did many, many, many years ago, in the sixties.

MOB: Do you write your pieces out?

MA: Sometimes I write about them, write lots of notes and drawings and things like that.

MOB: And do you write down the choreography?

MA: No, I don’t write step by step.

MOB: Even for a long piece like Monte?

MA: No, I don’t. I have the structures very clearly down in my mind. Unfortunately, many pieces now, over twenty years ago, I don’t remember. I remember their structures and the ideas and the feelings and some of the qualities of the movement, but I cannot remember some of the steps. The structures and the ideas, I do.

MOB: So, when you begin to work on a piece like Monte with the dancers, do you demonstrate, show them how to…?

MA: Oh, yes. Working with the music and tightening it up. It may work differently, I’m doing it now with the Washington Ballet and some of them might be doing it on points, it’s going to be very different. Also, they don’t work the same way, there’s not the same abandonment, there’s a different emphasis. This piece has a lot of weight to it and abandonment and a timing that a modern dancer understands but not classical dancers. But a good dancer is a good dancer, I think, with a good understanding of what I’m trying to do. It’s a very rich piece, Monte. I wanted to do it with nine dancers and ended up using seven because, as I said, there were accidents and lack of money. But I might do it with nine dancers and it’s going to be slightly different.

MOB: You’d have to incorporate the new steps and the new movements.

MA: Basically it is the same piece and it has the same structure, it’s just that things visually will be better. It will be harder to do in a smaller space because there’s more people. It could be, you know, a smaller version and a bigger version.

MOB: Basically, your own creative process has been ongoing, developing, blossoming, over the last twenty years.

MA: I’d like to think of that, yes. I think I am a better choreographer now. Again, it surprises me now how, with the knowledge that I had then, I did those pieces, so obviously I was following some good instincts, because I don’t always know what I’m doing. When I started choreographing I worked very hard and knew how to edit what I liked and what I didn’t, what was important and what was not, and now that I’m doing a revival I’m surprised, I mean, how I did some of the solos. I was not a mature choreographer by any means, yet today they look like mature works, so that pleases me.

MOB: But it sounds like you had a grasp, an intuitive grasp of your vocabulary, you didn’t have the wrong training, had been a dancer for many, many years…

MA: It’s a craft and it’s very difficult. The more I know, the more I realize I’m just beginning to learn.

MOB: It’s really like a special way of thinking.

MA: You have to listen to that. Otherwise, it’s just a formula. I think my work has been always known to be individual and original in that sense. It’s probably a lot of the process…

MOB: …the actual working out, because it basically is a communal art, you’re depending on other people, to work it out.

MA: They give a shading, a color. I look at them and see how they would look good. Something that would be very honest would come out of them and I try to get that out, to put them in a spot… Sometimes confessionary, trying to get things out of them. It’s hard nowadays, again, because of the fact that dancers don’t have what is called “staying power” because of economic reasons. It’s better if there’s a sympathetic family here working with me all the time for years and years and years, that way we get to know each other and then there would be more contribution from their end. But I find that hard because of the times.

MOB: For somebody like you, who’s spiritual, with your sense of meaning and aspiration, does that mean that some dancers wouldn’t be able to dance your pieces or do your theatre work?

MA: Oh, there’re some people that would not fit, absolutely…

MOB: Because they do not understand it.

MA: Because their interests are just in the more superficial things. It takes a certain kind of dancer to do my work. First of all, they have to have an appetite for movement, because, as you’ve noticed, my work is physical.

MOB: Energetic.

MA: Very energetic and physical and I like that, I believe in that. I also do minimal dances, as you saw in the same program, there were some solos that are very minimal and I’ve done some group pieces that are minimal. I want dancers that understand the range and can speak in that dimension that is other than just the factual, the fact. I don’t like them to be emotional, there’s more power when they’re not emotional. Holding tightly to their emotions, there’s more provocation by doing that. If you start dancing emotionally, to me it ruins my pieces.

MOB: You need an internal connection.

MA: I need to have people that can hold tightly to their emotions and understand the meaning of holding tightly to their emotions so that they can convey and communicate the inner life of movement. To me, the most important thing about a movement wasn’t so much that it was unusual; it has the proper ingredient in movement, of what I call the inner life of movement. A movement is faked, you can do the weirdest trick in the world and, if it’s faked, it has no communication. It has to have the right amount of inner life for it to speak to an audience. How I put it together is what makes it gel. That’s why it’s very fragile, because I can think of weird stuff just to be different but that doesn’t speak, after a while you get tired and bored if it’s faked. You have to really do the right connection of the inner life of the movement, which I find is the most difficult thing, especially for dancers who come in and out. They have to get inside my head to understand what I mean, I have to know them so I can get inside their bodies and try to get that dimension that speaks. Not an easy thing, it’s a fragile thing. Sometimes the music helps, sometimes whatever I say to them. They know now, this group, what I don’t like. Some of them came from other backgrounds, where there’s a lot of acting in the dancing and it took me a while to scrub them out of that, because I don’t want any acting in my dancing. Particularly in a piece like Quintet, which is a piece in black; there was a lot of acting at first, when they were doing it. I had asked them to learn it from a video while I was away and I came back and they were acting and dancing, it was not my piece! You have to make it yours first, stop acting, start living it, bringing the inner life of the movement to the movement itself. Then, when there’s that clarity to it, then we begin to mature with the piece. Otherwise, it’s just you superimposing something else onto it, about your steps. It took a while because, as I said, some of them had not worked with me before, but they understand now where I’m coming from. It’s clearer that way, something more honest comes out and the audiences are usually more convinced and it’s more believable. If it isn’t honest, it doesn’t work for me.

MOB: Your ideal would be to have a company of dancers who work for you over a long period of time…

MA: And are sympathetic to my beliefs. That would be the best, so we don’t have to waste so much time working hard. A lot of things get in the way but when you know somebody you go straight to the point, you can trust them.

MOB: Have you had that at some moment of your life?

MA: Yes, I have. I have worked with many beautiful people. Unfortunately, today is a different game, very few people, and even people that are getting paid a lot, the companies, do not stay, I don’t know what it is. They hop around too much. Very few dancers have a need to really dig deeply.

MOB: Into their own process.

MA: Into their own process, yes. You have to really stimulate them to do that. Felice has been with me for twenty-one years, she is doing that. There are a lot of very good dancers in New York today, technically much better than before, but very few have that staying power, that personal need to develop in a more honest way or aim for excellence. There’re so many different schools of thought, too; people are confused. Dancers that have a lot of talent don’t really know which direction to go to. It’s unfortunate, in a way, because time goes and now is the most important moment for a dancer. But I think in all performing arts this is true, a good actor has the same thing. In dance, which is a very physical thing, the body cannot lie. You have to be very relaxed, very mature and very much in touch with yourself so that you go straight to the point and that’s the kind of work that I like to do. Sometimes you have to go around, in order to make them aware that they are not doing it right, so that they can strip everything else off and get to the point. Telling somebody else to relax, you know, it’s very hard to tell somebody to relax and somebody else to obey. It has to come from within them.

MOB: Having a company is a real complex situation.

MA: Especially if you have a mind like mine. You can do formula dancing, which a lot of people like also, but I am more traditional in the sense that I like to dig and try to get to when things are really gelling, working, that’s what I want. I believe in work. I believe that nothing good comes without working. My philosophy has basically not changed in twenty-five years. I think my work is better, I listen and trust those things that I do not know about, that I sense, that I feel, that I can put across, and I have to get those things, get them out and make the invisible, visible. W-O-R-K.

MOB: Hard work!

MA: Not find a shortcut nor a short way of doing it. You have to be into your center, you have to be in touch with yourself. You would not so much understand this when you are young, the older you get you know how to get to that point. That’s what keeps me going, I still believe in this. I believe that dance speaks itself. I guess if I just had a formula that tells exactly how you have to do it, I would be bored with it. I try to respond to something that can speak to us through movement. It’s a different thing doing solos for myself, a different art, completely, than doing group dances. I have to wear different hats when I do both, but I still listen to the same reservoir. I don’t really have a formula, but you can see my works and there’s definitely a signature.

MOB: Do you think your own solo pieces are a more pure expression of your soul, sensibility, than the group pieces, in some way?

MA: Oh, I don’t know, that question. I think now I’m more confortable doing groups. When I was younger I found it very difficult. It was always very strange in the beginning that I found solo work much easier than group work. My colleagues, when I first started, they said, “oh no, don’t do groups, do solos.” I just locked myself in and think and criticize myself, for hours and hours and hours, and come out with something. It was easier for me to send messages through my own body than it was to send to other people. I have a group of people that I’ve worked with for about four years, they’re my students and because of that I just put my feelings into it and the group works very hard. They knew my language by then. It was not like just grabbing a lot of dancers; the difficult thing to do is go to a company like I’ve done in the past and I’m doing now, brand new dancers, and set a piece on. Especially when they’re used to a repertory, it’s very hard, you have to first convince them of what you are doing.

MOB: This is what you’ve been doing in Washington.

MA: Yes.

MOB: And in Japan, just wanted to ask you briefly about your days there and the work that you were doing.

MA: Oh, that was great for me when I was there. The first time in my life I didn’t have to worry about money because it was a wonderful, generous grant and it was like “solo time”. All I did was study, choreograph, dance, lecture, teach. I was busy doing my thing. Here, I have to sit in my desk doing a lot of paper work all the time. In Japan, what was wonderful was that I could concentrate on the things that interested me. That was the old things. I found the old Edo, Zen-related arts, more modern than what was going as modern there today. It was so different for me that I could really enjoy studying all that. I found that there was a sensibility that I had here before. So it was universal. It was wonderful that I could focus and do that without worrying about money or anything like that.

MOB: Where you working with dancers there, doing choreography?

MA: I didn’t do too much of that because I’d travelled so far away to see something new or different from me and found other people there imitating what we were doing here. So I stayed away from that and concentrated on the “living national treasures”, people in the traditional dance rather than the “modern” dance or the classical dance. I concentrated on things like nihon buyo, jiuta mai, even potters, people in their nineties doing other things, craft. I concentrated on that and I think that opened up a lot of antennas for me and expanded my view of dance. Their folk dances are almost over a thousand years old. I got into all of that and that was wonderful for me.

MOB: Did you feel at home?

MA: I did, actually. Very strange, I think there must’ve been a Japanese part of me in another lifetime because it made a lot of sense. In fact, I talked a great deal with Buddhist monks, I would go to them, they would look at me, “where did you study Zen?” I had never studied Zen. So much of our conversations sounded like this is what Zen is about, they felt that I had studied and learned, but I never had, it was just my philosophy of dance and life. A lot of the things made sense to me.

MOB: You had a good connection.

MA: Oh, yes. Naturally. I’m going now to Thailand so I’m hoping to go to Japan and say hello to my friends there. Again, unfortunately, the Japanese are very much in love with anything that’s American or commercial or fashionable, so they’re still very hard on breakdancing and jazz dancing. Modern dance doesn’t have a strong following there but I met some very, very special people that do their own thing. Like, a living national treasure, these people are just incredible. You can see the masters at work so clearly and that’s valuable, observing, talking to them, taking their classes. I’ve been fortunate enough to do all that and opening my antennas to learn.

MOB: Thailand is going to be much the same?

MA: I don’t think so but I hope so. This is going to be an experience for me. I’m doing a production for the king, it’s his birthday and I’m doing my solos. Also, some teaching and lecturing, but I’m going to be there long enough and hope that my time is flexible enough that I can escape and take some classes, learn about them, their culture and their world, because I’ll be there for at least six to eight weeks. That should be a long enough period for me, yes.

MOB: Sounds wonderful.

MA: Yes. I don’t know about the performance for the king, I’ve never done that, but that should be interesting. When I’m working, I’m two hundred percent myself than I am as a tourist. So it’s going to be good. There is a universality to it that, before I went to Japan—because there was something “Japanese-y” about my work—, I never understood, because I didn’t know any more about Japan than most people do when I first got there. But there is a sensibility that’s universal. So I guess that was what the critic said there was “Japanese-y” about me. Then I went there, I could see what they were talking about.