Rescuing Forgotten Voices: An Interview with Olga Jiménez de Wagenheim

Olga Jiménez en entrevista publicada por la revista CENTRO JOURNAL, del Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Hunter College, New York. (Foto por Joy Yagid)

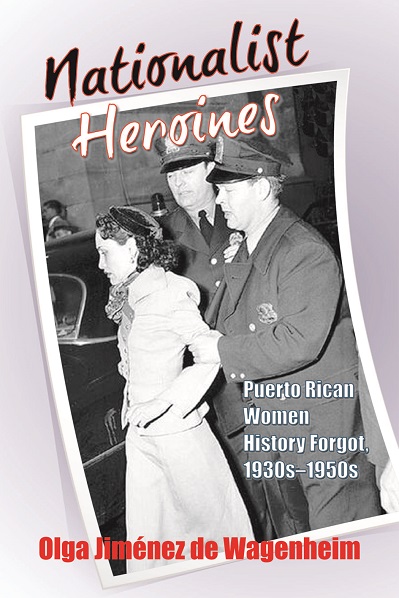

Jiménez de Wagenheim, a historian and long time director of the Puerto Rican Studies Program at Rutgers University, Newark, spearheaded the foundation of the New Jersey Hispanic Research and Information Center at Newark Public Library, including the creation of the Puerto Rican Community Archives. The archives aimed to document the historical legacy of Puerto Rican communities of New Jersey, a project to which Jiménez de Wagenheim contributed dozens of oral histories of Hispanic activists in New Jersey. More recently, she chronicled the fascinating and unfamiliar stories of numerous women engaged in the 20th century struggle for Puerto Rican independence.

Jiménez de Wagenheim’s new book, Nationalist Heroines: Puerto Rican Women History Forgot: 1930s-1950s, provides rich data on women’s understandings of themselves and their motivations to struggle for the liberation of Puerto Rico, with violence if necessary. Her study of 16 nationalist women opens windows to broader questions about the existing historiography on women, men and Puerto Rican history.

It not only corrects what was missing and overlooked, but also raises new questions for research. For example, Nationalist Heroines reveals with striking clarity the degree to which women described their political motivations in religious terms, and express an admiration for and devotion to Albizu Campos that might be described as religious in character. The way that religious fervor, sacrifice and martyrdom thread through all the stories of these women suggest the ways religion and religious ideologies have infused Puerto Rican struggles for justice long before liberation theology emerged from Medellín. Jiménez de Wagenheim’s documentation of the Nationalist women’s religiosity encourages us to take a second look at Albizu and his conversion to Catholicism while he was in the United States. Specifically, in conversation, she wonders what motivated that conversion and whether there might have been a connection to the Irish Republicans he met when studying in the Boston area, who were struggling for Irish independence in the early 20th century. Her work, therefore, serves an important role in filling a significant gap in the historiography of Puerto Rico and the nationalist movement. But more than informing us of what we didn’t know, it also challenges our understanding of the way we have understood the existing historical narrative.

I interviewed Jiménez de Wagenheim shortly after the release of her book in the summer of 2016 at her home in Millburn, New Jersey. I was interested in considering the book as an outgrowth of her earlier work on Puerto Rico’s struggle for independence (El Grito de Lares: sus causas y sus hombres [1984]; Puerto Rico’s Revolt for Independence: El Grito de Lares [1985]) and her own experience growing up in Puerto Rico in the 1940s and 1950s, when the Nationalist movement and the government crackdown were strong.

* * * *

Katherine T. McCaffrey (KTM): As a scholar, you have conducted archival research as well as spearheaded an oral history initiative in New Jersey to collect the voices and document the experience of the Latin American and Latino community. Your book combines both archival and oral history methods. Do you feel that you had a better understanding of the women you interviewed yourself?

Olga Jiménez de Wagenheim (OJW): Yes. There was an urgency and also an intimacy that developed when I was doing interviews with these women. It’s almost like you can sense when they’re telling you something that is very personal. Compared to what you find in the archives, I actually like doing oral history a lot.

KTM: Do you consider your book to represent a form of feminist scholarship?

OJW: I just felt that the story needed to be told because the women had always been looked at as auxiliaries, and I wanted to see whether that was the case or whether they had done more than help. And I think that they did a lot more than that. It’s rescuing the memory of their deeds.

KTM: You grew up in Puerto Rico during the time period that you discussed in your book.

OJW: I grew up in the hills. I grew up in a place called Puertos, Camuy. The population there was probably left over from the Taino Indians, and migrants from the Canary Islands. We lived way out in the country. We didn’t have running water or electricity until I was 14.

KTM: Growing up during this type period, did the historical events that you describe in the book permeate your consciousness?

OJW: Yes. Not during the time they were happening, but in retrospect. When I was growing up I was aware of the fact that there wasn’t a school in the place and then the PDP government built it. In my first few months in first grade, the books were in English—Fido and Jane and those kinds of readings. And then they disappeared very quickly, and then the books were in Spanish. Later on, when I started to research the history of Puerto Rico, I realized that 1948, which coincides with the year I went to school, was when the Puerto Rican government started issuing all the materials in Spanish. That was a transitional period when Puerto Rico was negotiating to become a Commonwealth, which now, of course, is in question. I felt the change. I no longer had to worry about Fido and Jane because I was going to learn about Pulgarcito, Arroz con leche, you know, the Spanish traditions.

KTM: As a child, do you remember if your parents supported Muñoz?

OJW: In my household, there were two pictures hanging in the living room. One was the Sacred Heart; the other was Muñoz Marín. My father’s life had been changed because of the policies that had been implemented by the PDP government. My father worked the land. Before he was able to obtain his own land, he worked for others, and during the Depression they paid him $0.25 a day. So when Muñoz came campaigning, he said to the people, this is what my father remembered: “We have to change this situation. We have to make sure you’re getting a minimum wage at least.” So by the time I left Puerto Rico in the summer of 1957, my father already owned some land, but if he worked for someone else, he earned the equivalent of three dollars a day. That’s a big difference. For him to see a school built where his children could go to school, a hospital in town where he could take his kids when they were sick was very important. Life changing.

Born in 1941, Jiménez de Wagenheim is the oldest of 7 siblings. An older sister died of mal- nutrition during the Great Depression. When Jiménez de Wagenheim was 14, her mother died in childbirth. Her father remarried the following year when she finished the ninth grade and there was no money to continue her education. An aunt in New York City offered to send her to school in the city. She lived in NYC for 2 1/2 years before returning to Puerto Rico where she attended college years later.

So off I went at age 15. I wasn’t quite 16 yet. I had just graduated 9th grade. I remember the flight was around seven hours, and I didn’t eat because I was afraid of getting sick. When I arrived, my aunt ordered pizza—I had never seen or heard of pizza, and I hated it! Because the sauce was sweet. That was an experience I remember.

KTM: Was it traumatic?

OJW: It was very traumatic. I was just coping. I was able to ride it out. My aunt was very kind, so that helped a lot.

KTM: What was it like arriving in New York City?

OJW: It was like going from here to the moon! You go from barrio Puertos where you just discovered electricity and running water, to Manhattan, 123 St.

My aunt was a very smart woman; she had a small import/export business with Mexico and had a little office in New York. She made sure to put me in Washington Irving High School, an all-girls school at the time. So I had to take the train from 123rd to 14th street. I think she showed me once, and that was it! I had to remember how to get back home. She would come home late, and I would wait for her by the EL station at 122nd, and we would walk home together and have dinner. The summer that I arrived she actually hired a young woman in our building to teach me the beginnings of English.

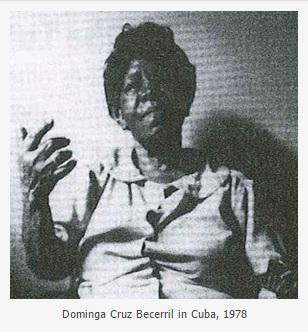

KTM: The book opens with the story of Dominga de la Cruz rescuing the flag. Can you talk about your decision to open the book with that story and what the Puerto Rican flag represented to Nationalists at that time?

OJW: Yes, I gave that a lot of thought because frankly she didn’t fit into the theme of women who went to prison, which is essentially the major focus of the book. But she’s considered one of the first women to sacrifice herself to save the Puerto Rican flag. The flag was a contested issue. It was designed in New York City in 1895 by members of the Puerto Rico Section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, who wanted to free Puerto Rico. So, the flag was very important. Carrying that flag, flying that flag, having that flag meant you could go to prison. For example, when Isabel Rosado was first arrested, the only thing the police found on her that could be used to charge her was a Puerto Rican flag in her pocketbook. So the flag was a very important symbol. And this woman Dominga actually left a place of safety—there was shooting going on—because she could not let the flag hit the ground. She ran into the gunfire to rescue the flag. To me, her action was very meaningful. So I thought the story ought to begin with her.

KTM: If you had the sources is there a particular woman you would like to explore?

OJW: I would like to know more about Rosa Collazo. She really touched me because she was an activist, but at the same time she was also a victim of the politics and the poverty in which she lived. I read her memoirs. They’re a little too sanitized. I’d like to know more, although now I don’t know if I have the energy.

KTM: Speaking of sanitized, a number of times when the Nationalists spoke about firing on Blair House, they spoke of it as a “demonstration.” In your research, in your interviews with the women, were there times that you felt that they were sugarcoating harsher truths?

OJW: That particular event: yes. I’m not sure if they were doing it on purpose. I’m not sure that was the case. It was their way of justifying what the four were doing. I would have liked the rawer word: they went there with the intent to assassinate the president. In fact a reviewer has already bawled me out for using the word assassinate and other words throughout the book that he would have preferred [to have been left out]. There are all kinds of interesting plays on language by the survivors of this movement, and certain words are not particularly liked. So these women use the word “demonstration” when I knew that was a euphemism.

KTM: Didn’t Lolita say she was aiming at the ceiling when she fired?

OJW: And she did. She was convicted of 9 of the 10 charges because the authorities were able to prove that 8 bullets from her pistol were actually encrusted in the ceiling. She always claimed that she went there to die, not to kill. The men, no. They didn’t make any of those allegations.

KTM: Among the rich sources of data in your book were the carpeta files that became available recently. Can you talk about what the carpetas: were, how you got access to them, and your impression of these files?

OJW: Carpetas were literally index files, a daily log of dissidents’ activities. Before you were indexed, the government kept track of your protest activity, for example, protesting in a student march. By the time you had three strikes against you, the police opened a carpeta, the most boring thing to read. But if you want to know about your daily activities, there is no better place to find it than in your carpeta! (Laughs) You may not remember that you had dinner with so and so at this place, but the people following you knew.

Jiménez de Wagenheim discussed how spying had always been part of the colonial regime in Puerto Rico, under both the Spaniards and the United States. The intensive surveillance of dissidents, however, emerged in the 1930s with the rise of the Nationalist movement.

OJW: The Nationalist Party was founded in 1922 to bring independence via the ballot. Then Albizu Campos became president in 1930, after a sojourn through different countries in Latin America. It’s the time of the Great Depression and a lot of things were going on in Puerto Rico: there was hunger; there were strikes; there was joblessness. Workers were protesting in the sugar fields, burning sugar plantations, and Albizu was saying that without independence the problems couldn’t be solved. The only way to get independence, he said, would be through armed struggle. He always made it clear: he would resort to armed struggle if necessary. By 1950 he found that armed struggle had become necessary. He claimed he had to take up arms because the United States had come up with the charade of the Commonwealth. As the good lawyer that he was—he was educated at Harvard—he saw that there very little change in the powers Puerto Rico received under the new government.

KTM: So how did it feel to look at these surveillance files, which you described it as kind of tedious?

OJW: Very tedious. You had informants, you had people who infiltrated the movement, and you had police agents who followed you. Spying on dissidents in Puerto Rico was one of the best jobs available. There were no jobs! But these people had jobs! Representative David Noriega, a lawyer and member of the Independence Party, waged a ten-year legal fight to get the carpetas released. When I first started researching the history of Puerto Rico back in the ‘70s, I didn’t even hear that these files existed. By the 1990s I heard through the grapevine that there were these documentos encadenados (chained files). So I couldn’t have done this book in the 1970s, because I wouldn’t have had access to the documents I needed. But because of David Noriega and several other individuals, the Puerto Rico courts finally released these documents from the Police Department where they had been kept in chains—encadenados—to the Department of Justice. The whole idea was that people who had been followed, who had been indexed, who had been “carpeteados,” should get their files back. But they only had six months to claim them. Many never got to claim them, but a few people did, like Isabel Rosado, Ruth Reynolds and Juanita Gonzalez.

For example, in Juan Alamo’s case, a Nationalist from Bayamón, who took care of López de Victoria’s two kids when he and his wife were sent to prison, it was his brother Pedro who was the informant! That just breaks your heart!

One thing that was interesting about the carpetas was that they were un-redacted, unlike the FBI files. So you could find the names of informants. For example, in Juan Alamo’s case, a Nationalist from Bayamón, who took care of López de Victoria’s two kids when he and his wife were sent to prison, it was his brother Pedro who was the informant! That just breaks your heart! His brother was giving information to the Secret Service, which it then shared with the FBI.

I never learned the names of the persons who reported on Don Pedro because they weren’t included, but their reports said: “well he just got a new refrigerator, got new towels…” details that can only be known by persons close to those being followed, persons no one suspects.

KTM: It sounds like it was a very visceral record of betrayal.

OJW: Yes, there was betrayal. The worst betrayal was the one by Lolita Lebron’s brother. When I found his depositions, which were given to the Puerto Rican police in San Juan over a three-day period in 1954, I was shocked. He just threw her under the bus. In exchange, he got a six-year suspended sentence. To think that he was the leader of the Nationalist movement in Chicago! So I quoted him quite extensively because I hadn’t seen his testimony anywhere else. I found a lot of stuff that was heartbreaking in many ways.

There were lies too. That’s where the spies placed you somewhere that you weren’t because they had to make a case. That was very common between ‘50 and ‘54. What happened was that in 1948 the PDP government passed the Gag Rule, Law 53, which was essentially a copy of the Smith Act, shortly after Don Pedro’s return to Puerto Rico in December of 1947. He was saying the time had come to make Puerto Rico indepen- dent just as Muñoz was moving into power and didn’t want anyone messing that up. The legislature passed this law, the Gag Rule, which said citizens couldn’t meet, write, print or advocate in favor of independence. The Nationalists revolted in October 1950, and by December 1950 the government amended the law. From then on, just belonging to any dissident group was prohibited—and those who did were subject to arrest. The Nationalists were considered a subversive group. But so were feminists, students, labor leaders and anyone who protested. It became a vicious cycle. Anyone who belonged to a “subversive” group could be arrested, and if convicted, could go to jail for one to 10 years.

KTM: One of the consistent themes of the book was the way this law was used to crush dissent. It seems ironic that this law was such a crucial mechanism for crushing opposition to Puerto Rico’s incorporation into to the United States with its ideals of freedom, civil liberties and so forth. How does this bitter irony shape your sensibility as a Puerto Rican and an American citizen?

OJW: It was a sad thing. First of all, remember that I grew up with my father. I grew up with this sense that the PDP government did all of these wonderful things for us. I remember as a child sitting on a blanket watching the movies the government sent to the rural areas once a month. My memory of that period was a pretty rosy one. Then I start reading this stuff. Not that I was naïve. As a university student, I had learned a lot and had protested the Vietnam War. But still I did not know the specifics about the PDP acts against the Nationalists. I did not know that Muñoz as the President of the Senate had pushed for the approval of the gag law because of his greed for power. He didn’t want anything to block his road to power. Motivations? You can only speculate. I tried to be fair. I tried to show both sides, including the ugly side of that particular period.

Other people who are in favor of independence have shown that side, but sometimes they hit you over the head with the information to such an extent that you say, “Wait a minute, there’s no balance here.” As a historian, I try to be balanced. It was difficult, very difficult. For example, I read Ángel Viera Martínez’s (one of the district attorneys) interrogation of Olga Viscal, and you could just see the cynicism, the hypocrisy, the twisting of her words. She was a 22-year-old student from the University of Puerto Rico who believed in independence, and who wanted her country to be free. She believed what Don Pedro was saying. She never committed any crimes. Yet she was sentenced to prison for 1 to 10 years for violating Law 53, and another three years for contempt of court. Why? Because she had the nerve to question the prosecutors, and to challenge the informants and the police for lying about her. So it was pretty ugly.

«For example, I read Ángel Viera Martínez’s (one of the district attorneys) interrogation of Olga Viscal, and you could just see the cynicism, the hypocrisy, the twisting of her words.»

KTM: Do you think the Nationalists ever had a chance of achieving independence?

OJW: I don’t think so. Had Albizu had the same ideas and had lived in the 19th century during the Grito of Lares, he would have made Puerto Rico independent. But by the time he came into history, the United States had just won the Second World War. The US had been exercising and growing its power since the 1890s and by 1950 had become a very powerful nation. I think Albizu himself knew he couldn’t win, but went ahead because of a question of … dignidad. It was a question of dignity. He wanted the world to know that there was a group of people on this island who did not want to go on being enslaved. He saw the Commonwealth as adding insult to injury. Not only was the place a colony, but now its people had been asked to consent to their own enslavement. And that’s what he hated about Muñoz. He felt that Muñoz had fallen into that trap.

KTM: When we’re talking about the Nationalist movement it is very much shaped by bitter struggles over the imposition of the Commonwealth status, but there’s also a broader global picture and post-War moment of decolonization and nationalist movements. How do you see that the Nationalists in Puerto Rico are connected to this larger context?

OJW: I haven’t done enough research on it, but as far as I’m concerned, Albizu’s lens was Latin America, except for Ireland. The struggle in Ireland coincided with his days at Harvard, where he actually met some of the people who were involved with the Irish Republican movement. He was an idealist when it came to the Irish Republic. The other thing about Albizu: he converted to Catholicism. Look at the contradictions of colonization. He was born extremely poor. He was a mulatto whose Spanish father didn’t recognize him until he graduated from Harvard. He didn’t get to go to school until he’s way past 11 or 12 years old, and it was an American religious group that interceded and helped him get an education. Of course he took advantage of it because he was a brilliant man. It was again a religious group that helped him get to the University of Vermont, and from there he got a scholarship to Harvard to study law. He served in the American armed forces during the First World War.

That whole transition of Albizu, from a bright young student with all kinds of promise to the radical leader that he became, has not been studied well enough. It seems that all the studies assume that Albizu was an independentista from the day he was born. That’s not the way life goes. That’s not the way things are. At some point he changes religion and becomes a Catholic. I don’t know what affiliation he was before. All I know is that it was one of the American Protestant religions, and he purposively changes his religion to Catholicism. Is it that he sees that the Irish have used religion as a rallying cause? I don’t know: but that would be a good question to explore. He also begins to embrace and romanticize the Spanish culture. I have studied the nineteenth century, and I know that the Spanish colonization was no better than the American; in some ways it was worse. But he had to hang onto these beliefs. the Catholic religion, the Spanish traditions and language, in order to fight the new enemy. Albizu is a fascinating figure who needs to be studied from different angles. I would love to know what was the relationship between him and the Irish Republicans. I can see that there might be a simpatía between the two, since both were oppressed by Anglos.

KTM: Many of the women in the book express an admiration for Albizu that is almost religious in character. In what ways do you think that Puerto Rican nationalism for these women was shaped by Catholicism?

OJW: Lolita actually saw Albizu as an incarnation of Jesus Christ. I don’t know if Carmín Pérez, for example, would have seen him that way. But they were all very religious. Isabel, Carmín went to church; they all went to mass. Spanish was a language of pride. You have to remember that Spanish in Puerto Rico did not become official until 1948. Even though one spoke it at home, it was not the language of instruction or recognized by the government. That changed in 1948, when the Muñoz government became the guardian of the island’s culture and language.

KTM: But in terms of this religiosity, do you think the men saw Albizu as Jesus Christ?

OJW: No. I couldn’t answer that categorically, but I don’t see it that way. For the women, it seems to me that there was this sense of sacrifice, which is ingrained in our Catholic culture. From the time you’re a little kid you are socialized to sacrifice yourself—the women—they have to be unselfish; they have to remain virgins; they have to be all these things.

That’s why the secret service tried to imply that the women were having love affairs with Albizu. That was not happening. They admired him because they felt that he sacrificed himself. He had sacrificed his legal career when he could have been making money. At one point Isabel [Rosado] bought him a pair of shoes with her little social worker’s salary because the pair he had didn’t fit him when his legs became swollen from the prison experiments. So they were all into this sacrifice stuff.

KTM: Didn’t Albizu himself say that the country is valor and sacrifice?

OJW: La Patria es Valor y Sacrificio. They took it very seriously. He did and they did. So to me those are religious concepts—the whole idea of sacrificio. While he was in jail he wrote a prayer for one of the women, for Doris [Torresola]; she had been shot. (Pause) A little too much for me, the religion thing! (laughs)

KTM: The other story I found particularly poignant was when you describe how Truman commuted the sentence for Oscar Collazo. You write:

President Truman signed an order (July 24, 1952) commuting Oscar’s death sentence to a life in prison. Coincidentally, the next day (July 25, 1952) the island would be celebrating its new status at the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Part of that day’s ceremony included flying the Puerto Rican flag (for which many nationalists had been arrested) alongside the American flag from every public building in Puerto Rico. Through that act, local rulers intended to dispel the image that the island was a colony of the United States, as it had been during the previous 54 years. For Oscar and his nuclear family, to have his life spared on the day that their beloved flag was being usurped by the same government that still kept so many of his comrades in jail “was a bittersweet pill to swallow,” according to his daughter Zoraida.

OJW: That was a great interview I had with Zoraida Collazo. She was actually crying when she told me this story. She said she was sitting in someone’s house in Bayamón, and all the television coverage was about this great celebration with the raising of the flag. Puerto Rico is going to be a Commonwealth. And then she heard about her father, that his sentence is going to be commuted. And she started running through the patio, crying because she didn’t know what was going on. It was very emotional, that interview with her. She said, “Why couldn’t it be done on another day, why did they need to link all of this together?” She was glad that her father was having his life saved, but then the irony that this was happening together. The next day, July 25th, the Nationalists were going to Guánica to protest the U.S. occupation of Puerto Rico. They’ve done that for years. They felt the commonwealth government as a slap in the face.

KTM: Puerto Rico is now facing devastating socioeconomic crisis: the economy is in recession; people are migrating in record numbers. As a historian, do you think there are any lessons from history to help guide our understanding of current events? What do you think it would take to turn around the current situation?

OJW: That’s the $64,000 question! I have to agree with the minority that the only way to solve this is to become independent. You can’t just keep begging for changes from the group that is never going to give you power. I don’t know that a revolution is necessarily going to make it possible, but if you are independent, you can make your own mistakes. You decide which way to go. But I don’t know that anyone in Puerto Rico is ready for change. The society is so divided. The problem with colonialism is that is so insidious. It corrodes your soul. And that is what you see—people are so divided. You give them enough of something to make them feel it is worthwhile, like American citizenship. You give them the opportunity to escape misery by coming to the United States, where then they can become full citizens and vote and all that. But the problem at home is not resolved. And I don’t know that it can be resolved because as I said, the society is completely divided. In my family, I’m probably the only one who believes in independence. The rest mostly favors of statehood. We don’t talk politics or religion in my family because then we can’t get into an argument. We know enough that we love each other too much to get involved in political arguments.

It is a very brutal time. I have a feeling that the leaders will find some way to patch things up. I think they are going to leave it for the next generation, but the problem is not going to be solved any time soon.

KTM: If Puerto Rico were to dedicate a national holiday to one of the women you profiled in your book, who would you like to see nominated and why?

OJW: It would be hard to choose one…but I would like to see Blanca Canales. I think that Blanca Canales was very clear about a lot of things and she was, in her own way, the leader of a lot of them. But then there’s a woman like Carmín Perez who was just totally devoted, not only to Don Pedro, but to the cause, and who walked the walk. She never wavered. And Ruth Reynolds also never wavered. That’s another very interesting woman. She had no need to be involved in that whole mess, and once she made the decision, which she did after a lot of thought and consideration, she accepted the repercussions. She died still believing that Puerto Rico ought to be independent. Every one of those women just offers you so much. I admire them because I would not be able to do any of the things they did! I don’t know what I would have done in their shoes! They are so clear that they get arrested not once, but twice and more, and they never waver. To me that’s admirable: their strength, their clear-headedness. The only time I had any kind of questions about them was their adoration of Albizu. He always spoke the truth and lived the ideal. But I guess I’m not the type who adores anyone. I’m always a bit more skeptical.

* Katherine T. McCaffrey ([email protected]) is an associate professor of anthropology at Montclair State University. She is the author of Military Power and Popular Protest: the US Navy in Vieques, Puerto Rico (Rutgers University Press, 2002), and numerous essays about Vieques’ post-navy struggle for social and environmental justice.

** Autorizada su reproducción, esta entrevista fue publicada originalmente en el CENTRO JOURNAL, volume xxix • number iii • fall 2017. Para suscribirse a CENTRO aquí.